ELA Curriculum Frameworks

The ELA/Literacy framework provides guidance around the implementation of the standards, particularly as it relates to the design and use of curriculum materials, instruction, and assessment.

The frameworks streamline a vertical application of standards and assessment across the K–12 continuum within Tier 1 of a Multi-Tier System of Support (MTSS), increase opportunities for all students, including multilingual learners and differently-abled, to meaningfully engage in grade-level work and tasks, and ultimately support educators and families in making decisions that prioritize the student experience. These uses of the curriculum frameworks align with RIDE’s overarching commitment to ensuring all students have access to high-quality curriculum and instruction that prepares students to meet their postsecondary goals.

To skip to a particular section of the frameworks, please use the following navigation links:

A PDF version of the ELA Curriculum Frameworks is also available to download.

If you would like to provide feedback on the ELA framework, you are welcome to do so through this online feedback form.

Section 1: Introduction

The Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE) is committed to ensuring all students have access to high-quality curriculum and instruction as essential components of a rigorous education that prepares every student for success in college and/or their career. Rhode Island’s latest strategic plan outlines a set of priorities designed to achieve its mission and vision. Among these priorities is Excellence in Learning. In 2019, Rhode Island General Law (RIGL) § 16-22-31 was passed by the state legislature, as part of Title 16 Chapter 97 - The Rhode Island Board of Education Act, signaling the importance of Excellence in Learning via high-quality curriculum and instruction. RIGL § 16-22-31 requires the Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education and RIDE to develop statewide curriculum frameworks that support high-quality teaching and learning.

The English Language Arts (ELA)/Literacy curriculum framework is specifically designed to address the criteria outlined in the legislation, which includes, but is not limited to, the following: providing sufficient detail to inform education processes such as selecting curriculum resources and designing assessments; encouraging real-world applications; being designed to avoid the perpetuation of gender, cultural, ethnic, or racial stereotypes; and presenting specific, pedagogical approaches and strategies to meet the academic and nonacademic needs of multilingual learners.1

The ELA/Literacy framework was developed by an interdisciplinary team through an open and consultative process. This process incorporated feedback from a racially and ethnically diverse group of stakeholders that included the Rhode Island Literacy Advisory board, students, families, the general public, and community partners.

1 The legislation uses the term English learners; however, RIDE has adopted the term multilingual learners (MLLs) to refer to the same group of students to reflect the agency’s assets-based lens.

Rhode Island students will be effective readers, writers, listeners, and speakers within society. Through the use of scientifically based strategies, we will build our students’ knowledge and understanding of literacy and the world to develop lifelong learners and engaged citizens.

The purpose of the ELA/Literacy framework is to provide guidance to educators and families around the implementation of the standards, particularly as it relates to the design and use of curriculum materials, instruction, and assessment. The frameworks should streamline a vertical application of standards and assessment across the K–12 continuum within Tier 1 of a Multi-Tier System of Support (MTSS), increase opportunities for all students to meaningfully engage in grade-level work and tasks, and ultimately support educators and families in making decisions that prioritize the student experience. These uses of the curriculum frameworks align with the overarching commitment to ensuring all students have access to high-quality curriculum and instruction that prepares students to meet their postsecondary goals.

Success Criteria

This framework should support educators in accomplishing the followng:

- Equitably and effectively support the learning of all students, including multilingual learners and differently abled students.

- Support and reinforce the importance of culturally responsive and sustaining education practices.

- Prepare students to thrive and succeed in college and/or careers.

The following five guiding principles are the foundation for Rhode Island's Curriculum Frameworks. They are intended to frame the guidance within this document around the use and implementation of standards to drive curriculum, instruction, and assessment within an MTSS. These principles include the following:

- Standards are the bedrock of an interrelated system involving high-quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

- High-quality curriculum materials (HQCMs) align to the standards and, in doing so, must be accessible, culturally responsive and sustaining, supportive of multilingual learners, developmentally appropriate, and equitable, as well as leverage students’ strengths as assets.

- High-quality instruction provides equitable opportunities for all students to learn and reach proficiency with the knowledge and skills in grade-level standards by using engaging, datadriven, and evidence-based approaches and drawing on family and communities as resources.

- To be valid and reliable, assessments must align to the standards and equitably provide students with opportunities to monitor learning and demonstrate proficiency.

- All aspects of a standards-based educational system, including policies, practices, and resources, must work together to support all students, including multilingual learners and differently-abled students.

A common misconception about school curricula is the belief that a curriculum is primarily the collection of resources used to teach a specific course or subject. A high-quality curriculum is much more than this. RIDE has previously defined curriculum as a “standards-based sequence of planned experiences where students practice and achieve proficiency in content and applied learning skills. Curriculum is the central guide for all educators as to what is essential for teaching and learning, so that every student has access to rigorous academic experiences.” Building off this definition, RIDE also identifies specific components that comprise a complete curriculum. These include the following:

- Goals: Goals within a curriculum are the standards-based benchmarks or expectations for teaching and learning. Most often, goals are made explicit in the form of a scope and sequence of skills to be addressed. Goals must include the breadth and depth of what a student is expected to learn.

- Instructional Practices: Instructional practices are the research- and evidence-based methods (i.e., decisions, approaches, procedures, and routines) that teachers use to engage all students in meaningful learning. These choices support the facilitation of learning experiences in order to promote a student’s ability to understand and apply content and skills. Strategies are differentiated to meet student needs and interests, task demands, and learning environment. They are also adjusted based on ongoing review of student progress towards meeting the goals.

- Materials: Materials are the tools and resources selected to implement methods and achieve the goals of the curriculum. They are intentionally chosen to support a student’s learning, and the selection of resources should reflect student interest, cultural diversity, world perspectives, and address all types of diverse learners. To assist local education agencies (LEAs) with the selection process, RIDE has identified and approved a collection of HQCMs in mathematics and English language arts (ELA) in advance of the 2023 selection and adoption requirement for LEAs. The intent of this list is to provide LEAs with the ability to choose a high-quality curriculum that best fits the needs of its students, teachers, and community. Each LEA must choose a curriculum from the list for core mathematics, ELA, and science content areas per the timelines outlined in RIGL§ 16.22.30-33. When possible, LEAs should adopt early because every student in Rhode Island deserves access to HQCMs.

- Assessment: Assessment in a curriculum is the ongoing process of gathering information about a student’s learning. This includes a variety of ways to document what the student knows, understands, and can do with their knowledge and skills. Information from assessment is used to make decisions about instructional approaches, teaching materials, and academic supports needed to enhance opportunities for the student and to guide future instruction.

Another way to think about curriculum, and one supported by many experts, is that a well-established curriculum consists of three interconnected parts all tightly aligned to standards: the intended (or written) curriculum, the lived curriculum, and the learned curriculum (e.g., Kurz, Elliott, Wehby, & Smithson, 2010). Additionally, a cohesive curriculum should ensure that teaching and learning is equitable, culturally responsive and sustaining, and offers students multiple means through which to learn and demonstrate proficiency.

The written curriculum refers to what students are expected to learn as defined by standards, as well as the HQCMs used to support instruction and assessment. This aligns with the ‘goals’ and ‘materials’ components described above. Given this, programs and textbooks do not comprise a curriculum on their own, but rather are the resources that help to implement it. They also establish the foundation of students’ learning experiences. The written curriculum should provide students with opportunities to engage in content that builds on their background experiences and cultural and linguistic identities while also exposing students to new experiences and cultural identities outside of their own.

The lived curriculum refers to how the written curriculum is delivered and assessed and includes how students experience it. In other words, the lived curriculum is defined by the quality of instructional practices that are applied when implementing the HQCMs. This aligns with the ‘methods’ section in RIDE’s curriculum definition. The lived curriculum must promote instructional engagement by affirming and validating students’ home culture and language, as well as provide opportunities for integrative and interdisciplinary learning. Content and tasks should be instructed through an equity lens, providing educators and students with the opportunity to confront complex equity issues and explore socio-political identities.

Finally, the learned curriculum refers to how much of and how well the intended curriculum is learned and how fully students meet the learning goals as defined by the standards. This is often defined by the validity and reliability of assessments, as well as by student achievement, their work, and performance on tasks. The learned curriculum should reflect a commitment to the expectation that all students can access and attain grade-level proficiency. Ultimately, the learned curriculum is an expression and extension of the written and lived curricula, and should promote critical consciousness in both educators and students, providing opportunities for educators and students to improve systems for teaching and learning in the school community.

Key Takeaways

- First, the written curriculum (goals and HQCMs) must be firmly grounded in the standards and include a robust set of HQCMs that all teachers know how to use to design and implement instruction and assessment for students.

- Second, the characteristics of a strong lived curriculum include consistent instructional practices and implementation strategies that take place across classrooms that are driven by standards, evidence-based practices, learning tasks for students that are rigorous and engaging, and a valid and reliable system of assessment.

- Finally, student learning and achievement are what ultimately define the overall strength of a learned curriculum, including how effectively students are able to meet the standards.

All of Rhode Island’s curriculum frameworks are designed to provide consistent guidance around how to use standards to support the selection and use of HQCMs, evidence-based instructional practices, as well as valid and reliable assessments — all in an integrated effort to equitably maximize learning for all students.

The curriculum frameworks include information about research-based, culturally responsive and sustaining, and equitable pedagogical approaches and strategies for use during implementation of HQCMs and assessments in order to scaffold, develop, and assess the skills, competencies, and knowledge called for by the state standards.

The structure of this framework also aligns with the five guiding principles referenced earlier. Section 2 lists the standards and provides a range of resources to help educators understand and apply them. Section 2 also addresses how standards support selection and implementation of HQCMs. Section 3 of this framework provides guidance and support around how to use the standards to support high-quality instruction. Section 4 offers resources and support for using the standards to support assessment. Though Guiding Principle 5 does not have a dedicated section, it permeates the framework. Principle 5 speaks to the coherence of an educational system grounded in rigorous standards. As such, attention has been given in this framework to integrate stances and resources that are evidence-based, specific to the standards, support the needs of all learners — including multilingual learners and differently-abled students — and link to complementary RIDE policy, guidance, and initiatives. Principle 5 provides the vision of a coherent, high-quality educational system.

In sum, each curriculum framework, in partnership with HQCMs, informs decisions at the classroom, school, and district level about curriculum material use, instruction, and assessment in line with current standards and with a focus on facilitating equitable and culturally responsive and sustaining learning opportunities for all students. The curriculum frameworks can also be used to inform decisions about appropriate foci for professional learning, certification, and evaluation of active and aspiring teachers and administrators.

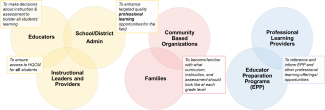

The primary audiences for the information and resources in the curriculum frameworks are educators in Rhode Island who make decisions and implement practices that impact students’ opportunities for learning in line with standards. This means that the primary audience includes teachers, instructional leaders, and school and district administrators.

However, the curriculum frameworks also provide an overview for the general public, including families and community members, about what equitable standards-aligned curriculum, instruction, and assessment should look like for students in Rhode Island. They also serve as a useful reference for professional learning providers and higher education Educator Preparation Programs (EPPs) offering support for Rhode Island educators. Thus, this framework is also written to be easily accessed and understood by families and community members.

Summary of Section Structure

| SECTION II: IMPLEMENTING A HIGH-QUALITY CURRICULUM | SECTION III: IMPLEMENTION HIGH-QUALITY INSTRUCTION | SECTION IV: HIGH-QUALITY LEARNING THROUGH ASSESSMENT |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| *Not applicable to all content areas |

Below are examples of how RIDE envisions the guidance and resources within this framework being used. These examples are not exhaustive by any measure and are intended to give educators an initial understanding of how to practically begin thinking about how to implement and use this framework to inform their daily practice.

Educators and instructional leaders such as curriculum coordinators, principals, and instructional coaches can use the curriculum frameworks as a go-to resource for understanding the HQCMs that have been adopted in their districts and to make decisions about instruction and assessment that bolster all students’ learning opportunities. For example, the frameworks can be used to:

- Unpack and internalize grade-level standards and vertical alignment of the standards;

- Analyze HQCMs and assessment(s) adopted in the district and understand how the standards are applied within the instructional materials and assessment(s);

- Norm on high-quality instructional practices in each of the disciplines; and

- Guide decisions related to instruction and assessment given the grade-level expectations for students articulated in the standards and the high-quality instructional materials.

Educators, curriculum leaders, and instructional coaches can use the curriculum frameworks as a resource when ensuring access to high-quality instructional materials for all students that are culturally responsive and sustaining, and that equitably and effectively include supports for MLLs. For example, the frameworks can be used to:

- Unpack and internalize English language development standards for MLLs; and

- Plan universally designed instruction and aligned scaffolds that ensure all students can engage meaningfully with grade-level instruction.

District and school administrators can use the curriculum frameworks to calibrate their understanding of what high-quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment should look like within and across disciplines and use that understanding as a guide to:

- Make resources available to educators, families, and other stakeholders in support of student learning;

- Norm “what to look for” in classrooms as evidence that students are receiving a rigorous and engaging instructional experience; and

- Structure conversations with teachers and families about high-quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

District and school administrators, as well as EPPs and professional learning providers, can use the curriculum frameworks to enhance targeted quality professional learning opportunities for the field. For example, the frameworks can be used to:

- Enhance educator or aspiring educator knowledge about the standards and pedagogical approaches used in Rhode Island;

- Roll out a vision for curriculum and instruction in the district, followed by curriculum-specific professional learning;

- Build capacity of educators and aspiring educators to engage in meaningful intellectual preparation to support facilitation of strong lessons;

- Aid educators and aspiring educators in making sense of the structure, organization, and pedagogical approaches used in different curriculum materials; and

- Build capacity of educators and aspiring educators to address individual learning needs of students through curriculum-aligned scaffolds.

Families and community organizations can use the curriculum frameworks to become familiar with what curriculum, instruction, and assessment should look like at each grade level.

Each content area (mathematics, science and technology, English language arts/literacy, history and social studies, world languages, and the arts) has, or will soon have, its own curriculum framework. For educators who focus on one content area, all information and resources for that content area are contained in its single curriculum framework. For educators and families who are thinking about more than one content area, the different content-area curriculum frameworks will need to be referenced. However, it is important to note that coherence across the curriculum frameworks includes a common grounding in principles focused on connections to content standards and providing equitable and culturally responsive and sustaining learning opportunities through curriculum resources, instruction, and assessment. The curriculum frameworks also explicitly connect to RIDE’s work in other areas including, but not limited to, MLLs, differently-abled students, early learning, college and career readiness, and culturally responsive and sustaining practices. Below is a brief overview of how this and the other curriculum frameworks are organized, as well as a summary of how the specific curriculum frameworks overlap and connect to each other.

| SECTION | WHAT IS COMMON ACROSS THE CONTENT AREA CURRICULUM FRAMEWORKS? | WHAT IS CONTENT-SPECIFIC IN EACH CONTENT AREA’S CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK? |

|---|---|---|

| Section 1: Introduction | Section 1 provides an overview of the context, purpose, and expectations related to the curriculum framework. | Each curriculum framework articulates a unique vision for how the framework can support high-quality teaching and learning. |

| Section 2: Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum | The introduction to this section defines how RIDE defines HQCMs in relation to standards. The final part of this section explains how HQCMs are selected in RI and provides related tools. |

The middle section of each curriculum framework has content-specific information about the standards behind curriculum resources and the vision for student success in the targeted content area. The final part of this section includes some specific information about the HQCMs for the targeted content area. |

| Section 3: Implementing High-Quality Instruction | This section provides an overview of how high-quality instruction is guided by standards and introduces five cross-content instructional practices for high-quality instruction. This section also includes guidance and tools to support high-quality instruction and professional learning across content areas. |

This section expands upon the cross-content instructional practices by providing content-specific information about instructional practices. This section also includes more specific guidance and tools for considering instruction and professional learning in the targeted content area. |

| Section 4: High-Quality Learning Through Assessment | The curriculum frameworks are all grounded in common information described here about the role of formative and summative assessment and how these align with standards. Some standard tools and guidance for assessment in any content area are also provided. |

Content-specific guidance about tools and resources for assessing students in the targeted content area are included in this section. |

This curriculum framework is designed to be a valuable resource for educators and families. It is intended to support classroom teachers and school leaders in developing a robust and effective system of teaching and learning. To achieve this, it also connects users to the vast array of guidance and resources that the RIDE has and will continue to develop. Thus, when logical, direct references are made, including direct hyperlinks, to any additional resources that will help educators, families, and community members implement this framework. Of particular significance is the link to college and career readiness.

College and Career Readiness

RIDE’s mission for College and Career Readiness is to build an education system in Rhode Island that prepares all students for success in college and career. This means that all doors remain open and students are prepared for whatever their next steps may be after high school.

Secondary education, which begins in middle school and extends through high school graduation, is the point in the educational continuum where students experience greater choice on their journey to college and career readiness. Students have access to a wide range of high-quality personalized learning opportunities and academic coursework, and have a variety of options available to complete their graduation requirements. To improve student engagement and increase the relevance of academic content, students may choose to pursue a number of courses and learning experiences that align to a particular area of interest, including through dedicated career and technical education programs or early college coursework opportunities.

Secondary level students have opportunities to be able to control the pace, place, and content of their learning experience while meeting state and local requirements. Rhode Island middle and high school students will have access to a wide range of high-quality early college and early career training programs that enable them to earn high-value, portable credit and credentials.

Kurz, A., Elliott, S. N., Wehby, J. H., & Smithson, J. L. (2010). Alignment of the Intended, Planned, and Enacted Curriculum in General and Special Education and Its Relation to Student Achievement. The Journal of Special Education, 44(3), 131-145. Retrieved from Alignment-of-the-Intended-Planned-and-Enacted-Curriculum-in-General-and-Special-Education-and-Its-Relation-to-Student-Achievement.pdf (researchgate.net)

Section 2: Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum

Having access to high-quality curriculum materials (HQCMs) is an important component of increasing equitable access to a rigorous education that prepares every student for college and careers. In answer to this national movement to increase access through high-quality materials, the State of Rhode Island, in 2019, passed RIGL§ 16.22.30-33. The legislation requires that all Rhode Island Local Education Agencies (LEAs) adopt HQCMs in K–12 schools that are (1) aligned with academic standards, (2) aligned with the curriculum frameworks, and (3) aligned with the statewide standardized test(s), where applicable.

RIDE uses various factors to determine high quality, primarily using information from EdReports, a non-profit, independent organization that uses teams of trained teachers to conduct reviews of K–12 English language arts (ELA), mathematics, and science curricula. Informed by EdReports as a baseline, RIDE’s list includes only curricula that are rated “Green” in all three gateways: (1 & 2) alignment to standards with depth and quality in the content area, and (3) usability of instructional materials for teachers and students. Because EdReports’ gateways comprise many indicators, which provide more in-depth looks across the integral components of instructional materials, it is important to note that having a “Green-rated” curriculum is a solid foundation, yet not enough on its own to ensure alignment to local instructional priorities and students’ needs. The curriculum adoption process should include consideration of an LEA’s instructional vision, multilingual learner (MLL) needs, and culturally responsive and sustaining education (CRSE). Selection is only the starting point in the larger process of adoption and implementation of high-quality instructional materials. LEAs should consider curriculum adoption and implementation an iterative process where the efficacy of a curriculum is reviewed and evaluated on an ongoing basis.

Coherence is one major consideration when adopting a new curriculum. One way of achieving coherence is the vertical articulation in a set of materials, or the transition and connection of skills, content, and pedagogy from grade to grade. Consideration of coherence is necessary to ensure that students experience a learning progression of skills and content that build over time through elementary, middle, and high school. As such, LEAs who consider the adoption of curriculum materials are cautioned against choosing a curriculum that is high quality at only one grade level, as it is likely it will disrupt a cohesive experience in the learning progression from grade to grade in the school or district.

While the standards describe what students should know and be able to do, they do not dictate how they should be taught, or the materials that should be used to teach and assess those (NGA & CCSSO, 2010). Curriculum materials, when aligned to the standards, provide students with varied opportunities to gain the knowledge and skills outlined by the standards. Assessments, when aligned to the standards, have the goal of understanding how student learning is progressing toward acquiring proficiency in the knowledge and skills outlined by the standards as delivered by the curriculum through instruction (CSAI, 2018).

No set of grade-level standards can reflect the great variety of abilities, needs, learning rates, and achievement levels in any given classroom. The standards define neither the support materials that some students may need nor the advanced materials that others should have access to. It is also beyond the scope of the standards to define the full range of support appropriate for MLLs and for differently-abled students. Still, all students must have the opportunity to learn and meet the same high standards if they are to access the knowledge and skills that will be necessary in their postsecondary lives. The standards should be read as allowing for the widest possible range of students to participate fully from the outset with appropriate accommodations to ensure maximum participation of students, particularly those from historically underserved populations (MDOE, 2017).

Having access to HQCMs is an important component of increasing equitable access to a rigorous education that prepares every student for college and careers.

Rigorous and comprehensive standards are the foundation for quality teaching and learning. The Rhode Island Core Standards for Reading, Writing, Speaking & Listening, Language, and Literacy in Content Areas, coupled with the implementation of high-quality curriculum materials, provide a vertical roadmap for school systems to empower literate and informed students. The standards articulate the knowledge and skills that students need to be prepared to succeed in college, career, and life. Whereas the high-quality curriculum materials when skillfully implemented by educators become the lever for students to master the ELA/Literacy standards. With these two components firmly established as non-negotiable inputs, educators and school and systems leaders can prioritize the implementation of rigorous, culturally, and linguistically responsive teaching. Educators can focus on assessment, then, is considered the critical output- a structured system to accurately and meaningfully measure student learning given the inputs.

When making a curriculum selection, a key priority should be on the comprehensiveness of the instructional materials. A comprehensive curriculum should:

- Include a distinct strand of the curriculum focused on explicit and systematic instruction in reading foundational skills, including a priority on phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding, morphology, semantics, and syntax.

- Prioritize both text complexity (predominantly through read-aloud in the primary grades) and volume of reading, such as through extended independent reading time, to build knowledge, vocabulary, verbal reasoning, and knowledge of language structure.

- Demonstrate coherence in the presentation of topics in order to grow content knowledge. Units are organized by topic, and topics are explored deeply and build on one another sequentially over the school year and across years. Reading and writing are integrated with science, social studies, music, and other content areas, to build content knowledge, rather than presented as atomized, skills-based activities.

- Include writing instruction that is embedded within the content of the curriculum, provides explicit writing instruction (e.g., sentence-level strategies), and capitalizes on the power of the planning and revision stages within the writing process.

- Provide a variety of formative assessments and performance assessments engaging students in the content of the unit.

The Rhode Island Board of Education approved the transition to the Rhode Island Core Standards for English Language Arts (ELA)/Literacy from the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) in March 2021 (Comparison Tables). Cohesive and aligned standards, curriculum, and assessment are critical to increasing student achievement. The Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy are tightly aligned to the assessments in the Rhode Island state assessment program, including the Rhode Island Comprehensive Assessment System (RICAS) assessment. These standards maintain the focus, coherence, and rigor of the CCSS while providing clarity and highlighting connections among the standards. (MA DESE, 2017)

College and Career Readiness (CCR) Anchor & Grade-Specific Standards

Collectively, the K–12 Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy provide a cumulative progression of standards designed to enable students to meet college and career readiness expectations no later than the end of high school. They are composed of both College and Career Readiness (CCR) anchor standards and grade-level standards. The CCR anchor standards and grade-specific standards are necessary complements — the former providing broad standards, the latter providing additional specificity — that together define the skills and understandings that all students must demonstrate. (CCSS) The CCR anchor standards ensure vertical coherence for the strands of Reading, Writing, Speaking & Listening, and Language. Within each strand, students are exposed to consistent anchor standards throughout the K–12 continuum.

To access the standards:

Rhode Island Core Standards for English Language Arts/Literacy

How to Read the Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy

The following are important points to keep in mind when reading the standards.

- Individual CCR anchor standards are identified by strand, CCR status, and number

- R.CCR.6, is decoded as the sixth CCR anchor standard for the Reading strand.

- Strand coding designations are found in [brackets] at the top of the page, to the right of the full strand title.

- Individual grade specific standards are identified by strand, grade, and number (or number and letter, where applicable)

- RI.4.3 is decoded as Reading: Informational Text, Grade 4, Standard 3; and,

- W.5.1a is decoded as Writing, Grade 5, Standard 1a.

- Grade Levels K–8; Grade Bands for 9–10 and 11–12

- K–8 standards are by individual grade level

- Except for 6–8 Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas, which is a band to allow for course flexibility

- 9–10 and 11–12 standards are by grade bands for all ELA/Literacy standards

- Provides course design flexibility

- K–8 standards are by individual grade level

(MA DESE, 2017)

What the ELA/Literacy Standards Do and Do Not Do

“The standards define what all students are expected to know and be able to do, not how teachers should teach. While the standards focus on what is most essential, they do not describe all that can or should be taught. A great deal is left to the discretion of the teachers and curriculum developers and coordinators.

No set of grade-level standards can reflect the great variety of abilities, needs, learning rates, and achievement levels in any given classroom. The standards define neither the support materials some students may need, nor the advanced materials others should have. It is also beyond the scope of the standards to define the full range of supports appropriate for [multilingual learners and differently-abled students]. Still, all students must have the opportunity to learn and meet the same high standards if they are to access the knowledge and skills that will be necessary for their post-high school lives.

The standards should be read as allowing for the widest possible range of students to participate fully from the outset and with appropriate accommodations to ensure maximum participation of [differently-abled students]. For example, for [differently-abled students] reading should allow for the use of Braille, screen-reader technology, or other assistive devices, while writing should include the use of a scribe, computer, or speech-to-text technology. In a similar manner, speaking and listening should be interpreted broadly to include sign language.

While the ELA and content area literacy components are critical to college, career, and civic readiness, they do not define the whole of readiness. Students require a wide-ranging, rigorous academic preparation and particularly in the early grades, attention to such matters as social, emotional, and physical development and approaches to learning.” (MA DESE, 2017)

“Students are expected to read extended texts: well-written, full-length novels, plays, long poems, and informational texts chosen for the importance of their subject matter and excellence in language use. Students build stamina by reading extended texts because such works often explore complex topics in ways that shorter texts cannot. Learning to persist in the reading of extended texts predisposes students to read for pleasure as adults and prepares them for academic reading in college, technical and professional reading in the workplace, and reading about issues of civic importance in the community.

Reading full-length works of fiction, drama, poetry, or literary nonfiction allows students to see how an author creates complex characters who change over time in response to other characters and events. In full-length informational texts, authors explore a topic in depth, with levels of argument, evidence, and analysis impossible in shorter texts. Moreover, these longer literary and informational texts often address challenging concepts and philosophical questions.

But of course, there is also a place for shorter texts, both in adult reading and in the curriculum. Literate adults keep current on world, national, and local events and pursue personal and professional interests by reading and listening to a host of articles, editorials, journals, and digital material. Teachers can build that habit in students and add coherence to the curriculum by ensuring that students read and listen to related shorter texts, such as articles or excerpts of longer works that complement an extended text. These shorter texts can serve a number of purposes, such as building background knowledge, providing a counterargument to the extended text, or providing a review or critical analysis of the longer text. Shorter selections can also show how the extended text’s topic is treated in another literary genre or medium, such as film or visual arts.” (MA DESE, 2017)

The Rhode Island Core Standards for Reading “place equal emphasis on the sophistication of what students read and the skill with which they read. Standard 10 defines a grade-by-grade ‘staircase’ of increasing text complexity that rises from beginning reading to the college and career readiness level. Whatever they are reading, students must also show a steadily growing ability to discern more from and make fuller use of text, including making an increasing number of connections among ideas and between texts; considering a wider range of textual evidence; and becoming more sensitive to inconsistencies, ambiguities, and poor reasoning in texts.” (MA DESE, 2017)

“All successful reading involves understanding the main ideas, themes, and details of a work. Reading Standard 1 through 3, under the cluster heading Key Ideas and Details, embodies this idea.

There are many approaches to critical reading; the Framework focuses on the two described below.

FORMAL ANALYSIS OR CLOSE READING

This approach focuses on determining what a complex text means by examining word choice and the structure of sentences. Most effectively applied to poetry or other short complex texts with multiple layers of meaning and nuanced vocabulary, or to excerpts from larger complex texts, this method of analysis is not appropriate for reading an entire extended text, because it slows readings and potentially leads them to miss an author's overarching ideas while focusing on details of vocabulary and syntax. Close reading is also an inappropriate and unnecessary approach to reading texts that are easy to understand.2 These are readily accessible texts for a grade level, characterized by literal ideas presented in a straightforward manner, with uncomplicated sentence structure and familiar vocabulary.

In English language arts classes, close reading is often a prerequisite to composing literary analysis. Close reading often involves re-reading a difficult passage several times in order to determine meaning — a useful practice to learn in grades K–12 and one that skilled readers employ automatically. This approach informs the wording of Reading Standards 4 to 6, grouped together under the cluster heading Craft and Structure. By design, these standards are echoed in Language Standard 1 through 6, which deal with standard English conventions, language and style, and vocabulary development.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

This approach is based on the concept that a reader gains an understanding of a text by setting it in a broader context. This often means comparing it to other texts and seeking similarities and differences among them. A variety of comparisons can be used, including, at the simplest level, comparing what the words in picture books say to what the pictures show. Other forms of comparison involve multiple works by one author, multiple texts on a similar topic or theme by different authors, multiple examples within and across genres, or multiple interpretations of a similar theme across media (e.g., print and video). Comparative analysis can also include examining the historical, political, and intellectually contexts of a work as well as using information from an author’s biography in an interpretation. This approach informs the wording of Reading Standards 7 through 9, with the cluster heading Integration of Knowledge and Ideas.” (MA DESE, 2017)

2 Timothy Shanahan at shanahanonliteracy.com (A Fine Mess: Confusing Close Reading and Text Complexity, August 3, 2016) and Marilyn Adams in American Educator (Advancing Our Students’ Language and Literacy: The Challenge of Complex Texts, Winter 2010–2011).

“Teachers expect students to write in school every day — short pieces about what they have read that might be completed in one sitting, and longer compositions that might take a week to a month or longer, with time for research, synthesizing information from multiple texts, drafting, revising, and editing. Cluster headings in the Writing Standards, therefore, include Text Types and Purposes, Production and Distribution of Writing, Research to Build and Present Knowledge, and Range of Writing.

The first three Writing Standards, under the cluster heading Text Types and Purposes, address in detail the components of writing opinions or arguments, explanations, and narratives. The intent of these standards is to promote flexibility, not rigidity, in student writing. Many effective pieces of writing blend elements of more than one text type in service of a single purpose: for example, an argument may rely on anecdotal evidence, a short story may function to explain some phenomenon, or a literary analysis may use explication to develop an argument. In addition, each of the three types of writing is itself a broad category encompassing a variety of texts: for example, narrative poems, short stories, and memoirs represent three distinct forms of narrative writing.

To develop flexibility and nuance in their own writing, students need to read a wide range of complex model texts. It is also important that students can discuss evidence from texts in formulating their ideas or positions, as well as demonstrate awareness of competing ideas or positions. The Writing Standards are therefore closely linked to the Reading and Speaking and Listening Standards.” (MA DESE, 2017)

For students to write every day within ELA classrooms and within content classes, it is important to note how the Writing Standards are dependent upon strong Language Standards instruction. The Language Standards include “the essential conventions of standard written and spoken English and aspects of vocabulary development, but also approach language as a matter of craft, style, and informed choice among alternatives.” (MA DESE, 2017)

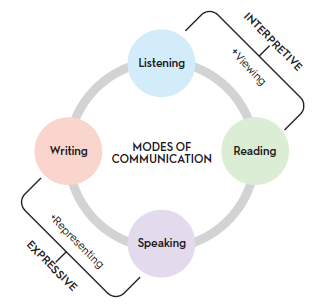

“Students are expected to discuss their school experiences in the curriculum daily with their peers, their teachers, and their families. Speaking and Listening Standards 1 through 3 address conversation, collaboration, responding to media, and gaining information through listening and viewing and by identifying speakers’ points of view and evaluating their reasoning. Standards 4 through 6 address preparing and presenting oral and media presentations. The Speaking and Listening Standards are closely related to preparation for participation in civic life. They also, like the Writing Standards, link to the Language Standards’ expectations for making informed and effective choices in language use.” (MA DESE, 2017)

“Research, addressed most explicitly in Writing Standards 7 through 9, involves identifying a topic; selecting and narrowing a research question; identifying, reading, and evaluating source materials; and using these materials as evidence in an explanation or argument. Though the Writing Standards address the process of research most comprehensively, other strands also link to various components of academic research: for example, Reading Standard 7 and Speaking and Listening Standard 2 both focus on integrating content from diverse sources.” (MA DESE, 2017)

“The Language Standards address the use of standard English conventions (Conventions of Standard English, Standards 1–3) and the development of vocabulary (Vocabulary Acquisition and Use, Standards 4–6). Standard 6 emphasizes the importance of developing both general academic and domain-specific vocabulary as a cumulative process. The term ‘general academic vocabulary’ refers to high-frequency words and phrases that are used broadly across disciplines in mature academic discourse and that sometimes have distinctly different meanings depending on the discipline and context. This category includes words such as affect, analyze, argue, average, coincidence, compose, conclude, contradict, culture, effect, explain, foundation, image, integration, masterpiece, method, percent, region, research, and translate. ‘Domain-specific vocabulary’ words and phrases are relatively low-frequency terms that have a single, albeit important, meaning and are primarily used within one discipline. This category includes words and phrases such as glacier, personification, parallelogram, Revolutionary War, and abstract painting.

Literature on language acquisition often refers to words used in everyday conversations as ‘Tier One’ words, general academic vocabulary as ‘Tier Two’ words, and domain-specific vocabulary as ‘Tier Three’ words.3 Teachers of all disciplines should pay attention to making sure students understand the ‘Tier Two’ words they encounter and can use them properly when speaking and writing. ‘Tier Three’ vocabulary is best taught as students study individual subjects in the curriculum.” (MA DESE, 2017)

3 Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York, NY: Guilford.

Strong foundational literacy skills are the driving force for proficient reading and writing and a gateway for accessing grade-level standards. Without explicit, systematic instruction in these essential subskills of literacy, students, particularly students with language-based learning differences, will develop gaps in their knowledge that will widen over time.

Foundational Skills standards in grades K–2 articulate a focus on building print concepts, demonstrating an understanding of spoken words, syllables, and individual phonemes, and applying grade-level phonics and word analysis skills when decoding. The Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy include expectations for explicit instruction in a variety of phonics patterns (e.g., digraphs, vowel teams) as well as morphological units (e.g., prefixes, inflectional endings, suffixes) to support the highly reciprocal processes of decoding and encoding. Additionally, the standards articulate the need for recognition of irregularly spelled high-frequency words, which are recommended to be taught by attending to the regular and irregular sound/symbol correspondences within words rather than relying on sight memorization. Context clues are recommended by the standards to be used to confirm meaning but should not be used as a strategy to decode unknown words. Practicing these skills to automaticity with immediate corrective feedback leads to accurate, fluent reading to support comprehension.

“The standards in this section have been derived from the College and Career Ready Anchor Standards for Reading, Writing, and Speaking and Listening to apply to subjects other than English. They complement but do not take the place of the grade-level or course-level content standards or practice standards in any of the discipline specific standards.

Reading, writing, speaking, and listening in subjects other than English, should focus on understanding and practicing discipline-specific literacy skills, using reading selections characteristic of that field.

For example, a history or social studies class might include print and digital texts such as:

- Primary and secondary sources, including visual resources.

- Foundational political documents.

- Charts, graphs, timelines, maps, illustrations.

- Position papers, editorials, speeches.

- Analytical and interpretive articles and books for a general audience.

- Video documentaries on history and social studies topics.

A science class might include print and digital texts such as:

- Articles from scientific journals.

- Technical reports on research.

- Science articles and books for a general audience.

- Position papers and editorials.

- Video documentaries on science topics.

Writing in each subject area includes short and longer research projects culminating in papers or presentations designed to meet the conventions and standards of each academic field.

The Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas are written for grade clusters: 6–8, 9–10 and 11–12, and include:

- Reading Standards for History/Social Studies (RCA-H). The term ‘history and social studies’ is broad and includes political and cultural history, humanities, civics, economics, geography, psychology, archaeology, and sociology. Note that world languages are not included here because they have their own set of standards for communication and language.

- Reading Standards for Science and Technical Subjects (RCA-ST). The term ‘science and technical subjects’ is broad and includes biology, chemistry, earth and space science, technology/engineering, computer science, career and technical subjects, business, comprehensive health, dance, music, theatre, visual arts, and digital arts.

- Writing Standards in the Content Areas (WCA). The Writing Standards apply to all subjects listed above, as well as mathematics.

- Speaking and Listening Standards in the Content Areas (SLCA). Like the Writing Standards, these apply to subjects listed above, as well as mathematics.” (MA DESE, 2017)

“Content knowledge is the indispensable companion to improved reading comprehension, since a child needs background knowledge about a topic in order to identify the main ideas and details of an informational text, or to understand how and why events unfold in a historical novel.4 All through the elementary grades, students need to be immersed in classrooms, schools, and libraries that provide a wide variety of books and media at different levels of complexity in a variety of genres — both literature and nonfiction. They need daily activities in which they develop language skills, mathematical understanding and fluency, understanding of experimentation and observation in science, creative experience in visual and performing arts, and the ability to interact with the community in a variety of ways.

The K–5 standards include expectations for reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language applicable to a range of subjects, including ELA, social studies, science, mathematics, the arts, and comprehensive health.

The standards insist that instruction in reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language be a shared responsibility within the school. This is particularly important in middle and high schools, where students encounter several teachers from different academic departments daily. The grades 6–12 standards are divided into two sections: one for ELA; and the other for history/social studies, science, mathematics, and career and technical subjects. This division reflects the unique, time-honored place of ELA teachers in developing students’ literacy skills and literary understandings while at the same time recognizing that teachers in other disciplines have a particular role of developing students’ capacity for reading and writing informational text.

Part of the motivation for the standards’ interdisciplinary approach to literacy is extensive research establishing that students who wish to be college and career ready must be proficient in reading complex informational text independently in a variety of content areas. Most of the required reading in college and workforce training programs is informational in structure and challenging in content; postsecondary education programs typically provide students with both a higher volume of such reading than is generally required in K–12 schools and comparatively little scaffolding.” (MA DESE, 2017)

The RI Core Standards for ELA/Literacy are designed to be used together with all Rhode Island standards (e.g., RI Core Standards for Mathematics, WIDA, NGSS) to ensure students receive a well-rounded curriculum throughout their K–12 school experience.

4 Liana Heitin in Education Week (Cultural Literacy Creator Carries on Campaign, October 12, 2016) and Daniel Willingham in American Educator (How Knowledge Helps, Spring 2016).

For educators with one or more active MLLs on their roster, enacting standards-aligned instruction means working with both state-adopted content standards and state-adopted English language development (ELD) standards. Under ESSA, all educators are required to reflect on the language demands of their grade-level content and move MLLs toward both English language proficiency and academic content proficiency. In other words, every Rhode Island educator shares responsibility for promoting disciplinary language development through content instruction.

Fortunately, the five WIDA ELD Standards lend themselves to integration in the four core content areas. Standard 1 is cross-cutting and applicable in every school context, whereas Standards 2–5 focus on language use in each of the content areas. Standard 3 is dedicated to the language for mathematics. Educators of mathematics are thus expected to support Standard 1 and Standard 3 as part of their core classroom instruction.

Image Source: 2020 Edition of WIDA ELD Standards Framework

Each of the WIDA ELD Standards is broken into four genre families: Narrate, Inform, Explain, and Argue. WIDA refers to these genre families as Key Language Uses (KLUs) and generated them based on an analysis of the language demands placed on students by the academic content standards. The KLUs are important because they drive explicit language instruction in each of the content areas. For Standards 2–5, the distribution of KLUs is similar across grades 4–12, but this distribution varies in the early grades, with grades K–3 placing more emphasis on Inform than Explain and Argue. Of the four content areas, only English language arts features Narrate as very prominent..

Each KLU is further broken down by language function and feature. Language functions reflect the dominant practices for engaging in genre-specific tasks (e.g., students often orient audiences in narratives for ELA by describing the setting or characters). By contrast, the language features represent a sampling of linguistic and non-linguistic resources (e.g., connected clauses, noun phrases, tables, graphs) that students might use when performing a particular language function. Together, the KLUs, language functions, and language features capture what it would look and sound like for students to use language deftly in language arts. Please see below for an example of how these three elements appear in the WIDA ELD Standards.

Image Source: 2020 Edition of WIDA ELD Standards Framework

Curriculum Resources

Selecting and Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum In Rhode Island: A Guidance Document: This guidance document outlines the provisions of RIGL§ 16.22.30-33 with regarding adopting high-quality curriculum and includes a list of approved curricula for ELA and Mathematics.

Curriculum Used in Rhode Island: This list and visualization displays which K–12 curricula are being used in each LEA and designates their quality as either red, yellow, green, not yet rated, or locally developed.

Resources to Support Standards

| RESOURCE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Rhode Island Core Standards for English Language Arts/Literacy | Standards Document: Grade-level and grade-span standards K–12 for ELA/Literacy including Reading Literature & Informational Texts, Writing, Speaking & Listening and Language. And Literacy in the Content Areas (6–12) including Reading, Writing, and Speaking & Listening. |

| Common Core State Standards / Rhode Island Core Standards Comparison Tables K–12 English Language Arts | Standard-by-standard comparison tables to highlight the differences in content between the CCSS and the Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy. These tables should assure users of high-quality instructional materials of the overall alignment, while providing guidance on where minor adjustments may need to be made within instruction. |

| Vertical Standards Progressions | Documents that articulate the vertical standard progression within each standard strand for ELA/Literacy. |

| Quick Reference Guides | Reference Guides provide explanations of text complexity, what it is and its implications for instruction and student learning. |

K–5 Standards Support Materials

|

Support Materials that help to elaborate and define the Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy for Grades K–5. |

6–12 Standards Support Materials

|

Support Materials that help to elaborate and define the Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy for Grades 6–12. |

| RIDE Resources: Academic Vocabulary, Close Reading, Text Dependent Questions, Writing and Argument Modules | Professional Learning Modules to deepen understanding of the shifts within the CCSS. |

| Structured Literacy | Instructional examples and tools to support classroom instruction. |

| RI Comprehensive Literacy Guidance | Guidance document: The RICLG supports educators in understanding the components of literacy and implementation of best practices in daily instruction. Included are strategies, methods, and resources for assessment, intervention, and content area literacy. |

| Personal Literacy Plans | Guidance document: A Personal Literacy Plan (PLP) is a plan of action used to accelerate a student’s learning in order to move toward grade level reading proficiency. Students in K–12 must have a PLP in place if reading below grade level, per legislation and the secondary regulations. |

Footnotes

Timothy Shanahan at shanahanonliteracy.com (A Fine Mess: Confusing Close Reading and Text Complexity, August 3, 2016) and Marilyn Adams in American Educator (Advancing Our Students’ Language and Literacy: The Challenge of Complex Texts, Winter 2010–2011).

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York, NY: Guilford.

Liana Heitin in Education Week (Cultural Literacy Creator Carries on Campaign, October 12, 2016) and Daniel Willingham in American Educator (How Knowledge Helps, Spring 2016).

References

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. (2017). Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks for English Language Arts and Literacy. Retrieved from https://www.doe.mass.edu/frameworks/current.html

The Center on Standards and Assessment Implementation (CSAI). (2018). CSAI Update: Standards Alignment to Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED588503.pdf

Section 3: Implementing High-Quality Instruction

As described in Sections 1 and 2 of this framework, while robust standards and high-quality curriculum materials (HQCMs) are essential to providing all students the opportunities to learn what they need for success in college and a career of their choosing, high-quality instruction is also needed. Standards define what students should know and be able to do. HQCMs that are aligned to the standards provide educators with a roadmap and tools for how students can acquire that knowledge and skill. It is high-quality instruction that makes the curriculum come alive for students. High-quality instruction gives all students access and opportunity for acquiring the knowledge and skills defined by the standards with a culturally responsive and sustaining approach. “When teachers have great instructional materials, they can focus their time, energy, and creativity on meeting the diverse needs of students and helping them all learn and grow.” (Instruction Partners Curriculum Support Guide Executive Summary, p. 2) Executive-Summary-1.pdf (curriculumsupport.org)

The process of translating a high-quality curriculum into high-quality instruction involves much more than opening a box and diving in. This is because no single set of materials can be a perfect match for the needs of all the students that educators will be responsible for teaching. Therefore, educators must intentionally plan an implementation strategy in order to have the ability to translate HQCMs into high-quality instruction. Some key features to attend to include:

- Set systemic goals for curriculum implementation and establish a plan to monitor progress,

- Determine expectations for educator use of HQCMs,

- Craft meaningful opportunities for curriculum-based embedded professional learning,

- Factor in the need for collaborative planning and coaching (Instruction Partners Curriculum Support Guide Executive Summary, page 4) Executive-Summary-1.pdf (curriculumsupport.org), and

- Develop systems for collaboratively aligning HQCMs to the WIDA ELD Standards.

Thus, with a coherent system in place to support curriculum use, teachers will be well-positioned to attend to the nuances of their methods and make learning relevant and engaging for the diverse interests and needs of their students.

Given the above, what constitutes high quality instruction? In short, high-quality instruction is defined by the practices that research and evidence have demonstrated over time as the most effective in supporting student learning. In other words, when teaching is high quality, it embodies what the field of education has found to work the best. Therefore, this section provides a synthesis of research- and evidence-based practices that the Rhode Island Department of Education believes characterizes high quality instruction in ELA/Literacy. This section begins by describing the high-quality instructional practices that apply across content areas and grades with details and examples that explain what these instructional practices look like in ELA/Literacy, and also explains other specific instructional practices that are at the core of high-quality instruction in ELA/Literacy. The instructional practices articulated in this section are aligned with and guided by best practices for multilingual learners and for differently-abled students, and specific information and resources are provided about how to support all students in their learning while drawing on their individual strengths. These instructional practices also contribute to a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) in which all students have equitable access to strong, effective core instruction that supports their academic, behavioral, and social emotional outcomes. This section on instruction ends with a set of resources and tools that can facilitate high-quality instruction and professional learning about high-quality instruction, including tools that are relevant across content areas and grade levels and those that are specific to ELA/Literacy.

In reviewing this section, use Part 2 to understand what high-quality instruction should look like for all students in ELA/Literacy. Use Part 3 to identify resources that can promote and build high-quality instruction and resources for learning more about how to enact high-quality instruction.

In order to effectively implement high-quality curriculum materials, as well as ensure that all students have equitable opportunities to learn and prosper, it is essential that teachers are familiar with and routinely use instructional practices and methods that are research- and evidenced-based. Below are instructional practices that are essential to effective teaching and learning and are common across all disciplines and curriculum frameworks. For additional guidance, there are also descriptions and references to instructional practices that support specific student groups, such as multilingual learners and differently-abled students.

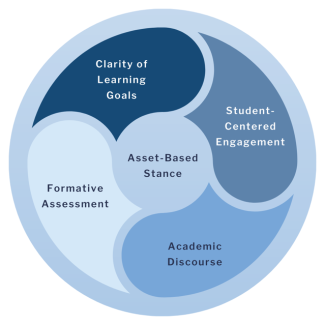

High-Quality Instruction in All Disciplines

Below are five high-quality instructional practices that RIDE has identified as essential to the effective implementation of standards and high-quality curriculum in all content areas (See figure to the right). These practices are emphasized across all the curriculum frameworks and are supported by the design of the HQCMs. They also strongly align with the instructional framework for multilingual learners, the high-leverage practices (HLPs) for students with disabilities, and RIDE’s teacher evaluation system. Below is a brief description of each practice and what it looks like in ELA/Literacy.

ASSETS-BASED STANCE

Teachers routinely leverage students’ strengths and assets by activating prior knowledge and connecting new learning to the culturally and linguistically diverse experiences of students while also respecting individual differences.

What This Looks Like in ELA/Literacy

Developmentally, students are naturally curious about learning new words, concepts, and ideas and making arguments with evidence to support their thinking. Students also bring a wealth of prior knowledge to new learning based on their lived experiences. Because of this, it is essential that teachers tap into this knowledge when embarking on a literacy unit or whenever appropriate during routine instruction. Inherent within the Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy is a focus on helping students increasingly be able to access and construct knowledge within and across content areas (e.g., mathematics, science, social studies) and grade-level texts. As teachers implement their high-quality curriculum materials, they must build upon and honor each student’s understanding and knowledge base to further their own understanding. Students' home language is also an asset that should be accessed to help build knowledge and understanding of language within the classroom.

What this looks like in relation to Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Differentiated core instruction based in UDL provides access and equity for each student providing multiple options for learning and expression without changing what is being taught. Differentiation is proactive with the goal of adjusting the how, based on understanding learner assets and needs, so students may achieve maximum academic growth. High-quality curriculum and instruction implemented through UDL and differentiation support access to grade-level curriculum as part of Tier 1 of a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS).

What this looks like for Multilingual Learners (MLLs)

Educators with MLLs in their class assume an asset-based stance will advance student learning. They can do this by drawing on MLLs’ home languages, academic and personal lived experiences, and world views, and the knowledge and skills used to navigate social settings. Although RIDE encourages student use of academic registers, it is important that educators and administrators maintain an asset-oriented stance in facilitating academic discourse and student understanding of standard English conventions, particularly when working with learners from minoritized groups. Educational agencies can play a role in sustaining the linguistic traditions of their students. Thus, classroom discourse, when done well, will reflect the discourse practices of local communities—capturing the rich ways families actually use language, rather than making prescriptive judgements about how students and their families ought to talk.

What this looks like for Differently-Abled Students (DAS)

Implementation of HLP 3: Collaborate with Families to Support Student Learning and Secure Needed Services promotes an assets-based stance for students with IEPs. Effective collaboration between educators and families is built on positive interactions in which families and students are treated with dignity. Educators affirm student strengths and honor cultural diversity maintaining open lines of communication with phone calls or other media to build on students’ assets and discuss supports or resources. Trust is established with communication for a variety of purposes and not just for formal reasons such as report cards, discipline reports, or parent conferences. In ELA, this could mean learning from communication with the families that one student enjoys reading or listening to non-fiction text while another student thrives when writing creatively. These areas of strength can create bridges to areas of needed support for DAS.

To Learn More

Below is a variety of links to resources to learn more about this practice.

| RESOURCE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 3 Steps to Developing an Asset-Based Approach to Teaching | Article on how to build upon what your students bring to the classroom |

| Five Ways to Build an Asset-Based Mindset in Education Partnerships | Article on developing an asset-based mindset |

| An Asset-Based Approach to Support ELL Success | Article on strategies for engaging and supporting MLLs |

| HLP #3: Collaborate with Families to Support Student Learning and Secure Needed Services | Leadership Guide for HLP #3: Collaborate with Families to Support Student Learning and Secure Needed Services |

| Stories from the Classroom: Focusing on Strengths within Assessment and Instruction | Progress Center | Video from Progress Center on including students in examining their data and setting ambitious goals by focusing on their assets |

| TIES TIPS | Foundations of Inclusion | TIP #6: Using the Least Dangerous Assumption in Educational Decisions | Institute on Community Integration Publications (umn.edu) | Article on how the least dangerous assumption pushes educators to consider all students as capable. The challenge is to replace a deficit mindset and consider what can educators do to support students in how they access, engage in, and respond not only to both academic and life skills content |

| Beyond IEPs and 504 Plans: Why You Should Consider Asset-Based Accommodations | Article on how asset-based accommodations beyond IEPs and 504s can be effective tools for supporting academic achievement and future success |

| Classroom Supports: Universal Design for Learning, Differentiated Instruction CTE Series 3 | NTACT:C (transitionta.org) | Webinar on the CAST framework of UDL and explanations for how one district incorporates UDL into their CTE programs |

| MTSS for All: Including Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities | Brief from the TIES Center that provides suggestions for ways in which MTSS can include students with the most significant cognitive disabilities |

CLEAR LEARNING GOALS

Teachers routinely use a variety of strategies to ensure that students understand the following:

- What they are learning (and what proficient work looks like),

- Why they are learning it (how it connects to what their own learning goals, what they have already learned and what they will learn), and

- How they will know when they have learned it.

What This Looks Like in ELA/Literacy

The Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy articulate clear, consistent expectations about knowledge, skills, and practices students should know and be able to do at each grade level. As teachers prepare for and implement high-quality instructional materials, it is imperative that they have a full understanding of the depth, breadth and rigor of each standard in order to make efficient and effective decisions within instruction. Instructional materials that have met the benchmark of high quality, should include clear learning goals aligned with the Rhode Island Core Standards. It is within the teacher’s implementation of the high-quality instructional materials that they articulate the clear learning goals consistently throughout the teaching and learning so that students always know what they are expected to learn, why it is important, and how they need to demonstrate it. Teachers utilizing their deep knowledge of the standards, coupled with their use of high-quality instructional materials and their knowledge of current student understanding will enable them to achieve the learning goals and student proficiency by providing clear systematic and explicit instruction.

What this looks like for Multilingual Learners (MLLs)

For educators with one or more active MLLs on their roster, clear learning goals for MLLs will consist of explicit language goals to guide instruction in ELA/Literacy. Educators will model effective use of disciplinary academic vocabulary and syntax, creating opportunities every day for explicit disciplinary language development, aligned to the WIDA ELD Standards.

What this looks like for Differently-Abled Students (DAS)

HLP 14, Teach Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies to Support Learning and Independence, supports the high quality instruction practice of Clear Learning Goals. Through task analysis, educators can support DAS by determining the steps they need to take to accomplish goals, then create and teach a procedure to help the student meet the goals. The educator uses explicit instruction (HLP 16) to teach the student self-regulation strategies such as self-monitoring, self-talk, goal-setting, etc. Clear, step-by-step modeling with ample opportunities for practice and prompt feedback coupled with positive reinforcement (HLP 22) in different contexts over time ensure that DAS become fluent users of metacognitive strategies toward understanding and achieving learning goals. For example, when writing in science or social studies, the Self-Regulated Strategy Development approach can support DAS to achieve content area writing goals.

To Learn More

Below is a variety of links to resources to learn more about this practice.

| RESOURCE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| High-Leverage Practice (HLP) Leadership Guides from the Council for Exceptional Children | Leadership Guides for the following HLPs: #11: Identify and Prioritize Long- and Short-Term Learning Goals #12: Systematically Design Instruction Toward Learning Goals #13: Adapt Curriculum Materials and Tasks #14: Teach Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategie to Support Learning and Independence #16: Use Explicit Instruction #22: Provide Positive and Constructive Feedback to Guide Students’ Learning and Behavior (academic) |

| High-Leverage Practice Videos for HLP #11 and HLP #16 | Videos highlighting HLP #11 (identify and prioritize long- and short-term learning goals) and HLP #16 (use explicit instruction) found under “Access Videos.” |

| Culturally Responsive Teaching for Multilingual Learners: Tools for Equity | Videos to support culturally responsive teaching that showcase strategies, such as activating background knowledge and partnering with MLL families. |

| Stories from the Classroom: Focusing on Strengths within Assessment and Instruction | Progress Center | Video from Progress Center on including students in examining their data and setting ambitious goals |

| Intensive Intervention Course Content: Features of Explicit Instruction | National Center on Intensive Intervention | Course content to support educators in providing explicit instruction in whole groups or small groups |

STUDENT-CENTERED ENGAGEMENT

Teachers routinely use techniques that are student-centered and foster high levels of engagement through individual and collaborative sense-making activities that promote practice, application in increasingly sophisticated settings and contexts, and metacognitive reflection.

What This Looks Like in ELA/Literacy

The Rhode Island Core Standards for ELA/Literacy include standards for Reading, both Literature and Informational Texts, Writing, Speaking & Listening, Language, and Literacy in the Contents. As teachers engage students within all the literacy strands, they need to ensure that students are active participants in their learning. High-quality instructional materials include a plethora of materials and options from which educators make professional decisions regarding selecting what components and which instructional strategies would best support their students for success.

Student-centered engagement within ELA/Literacy instruction examples include by are not limited to:

- Multisensory foundational skills activities that incorporate visual, auditory, and kinesthetic/tactile modalities (e.g., utilizing Elkonin boxes in kindergarten for phonemic awareness practice),

- Read alouds, multiple reads, access to audiobooks that build students’ background knowledge and vocabulary and/or understanding of the author's craft,

- Pairing fiction/nonfiction texts to build students’ content knowledge,

- Engage students to activate their prior knowledge,

- Student texts are relevant, challenging, worthwhile, and reflective of their own experience and pushing students to learn about others’ experiences,

- Students are exposed to multiple modalities and mediums for analyzing text (e.g., art, music, popular culture),