Early Learning Curriculum Frameworks

The Early Learning framework provides guidance around the implementation of the RI Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS), particularly as it relates to the design and use of curriculum materials, instruction, and assessment.

The frameworks streamline a vertical application of standards and assessment across the Birth through age 5 continuum within Tier 1 of a Multi-Tier System of Support (MTSS), increase opportunities for all students, including multilingual learners and differently-abled, to meaningfully engage in grade-level work and tasks, and ultimately support educators and families in making decisions that prioritize the student experience. These uses of the curriculum frameworks align with RIDE’s overarching commitment to ensuring all students have access to high-quality curriculum and instruction that prepares students to meet their postsecondary goals.

To skip to a particular section of the frameworks, please use the following navigation links:

PDF versions of the Early Learning Curriculum Framework are also available to download in English and Spanish.

Section I: Introduction

The Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE) is committed to ensuring all students have access to high-quality curriculum and instruction as essential components of a rigorous and relevant education that prepares every student for success in college and/or their career. Rhode Island’s latest strategic plan outlines a set of priorities designed to achieve its mission and vision. Among these priorities is Excellence in Learning. In 2019 Rhode Island General Law (RIGL) § 16-22-31 was passed by the state legislature, as part of Title 16 Chapter 97 - The Rhode Island Board of Education Act, signaling the importance of Excellence in Learning via high-quality curriculum and instruction. RIGL § 16-22-31 requires the Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education and RIDE to develop statewide curriculum frameworks that support high-quality teaching and learning.

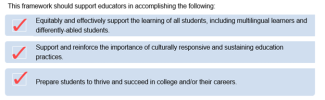

The Early Learning curriculum framework, for children ages Birth through 5, is specifically designed to address the criteria outlined in the legislation, which includes but is not limited to, the following:

- Informing education processes such as selecting curriculum resources and designing assessments

- Encouraging real world applications of standards-aligned curriculum, instruction, and assessment

- Countering the perpetuation of gender, cultural, ethnic or racial stereotypes

- Presenting specific, pedagogical approaches and strategies to meet the academic and nonacademic needs of multilingual learners.

The Early Learning framework was developed by an interdisciplinary team through an open and consultative process.

In the 2020-21 school year there were approximately 70,220 children ages Birth through age five in Rhode Island. 39% (27,344) of these children reside in one of the state’s four core cities, consisting of Central Falls, Pawtucket, Providence, and Woonsocket. As of the 2021-22 school year, 30.5% (21,459) of the Birth through Five population were enrolled in a licensed community-based early learning program, child care or family childcare home, 1.7% (1,205) in Head Start, and 4% (2,834) received preschool services in Rhode Island public schools (RI KIDSCOUNT, 2022). The Department of Human Services, who oversees these licensed programs, works collaboratively with RIDE to ensure early learning programs throughout the state continuously increase quality and improve the education provided to children aged birth through 5. Through the BrightStars Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS), both center-based and Family Child Care providers are encouraged to increase their star rating (quality rating), in turn receiving higher child care subsidy rate.

RI Pre-K. RI Pre-K provides free, high-quality Pre-K education to eligible four-year-old children. RI Pre-K is offered through a unique, mixed-delivery model comprised of Head Start programs, local education agencies/school districts, and community-based childcare providers. RI Pre-K programs are awarded through a competitive grant application process that evaluates the organization’s demonstrated ability and experience to provide a high-quality early childhood program and a commitment to continued quality improvements. Providing access to voluntary, free, high-quality pre-kindergarten programs is a strategy proven to help close the achievement gaps that are noticeable even before children enter school and to provide increased educational opportunities to students.

Multilingual Learners. The term “multilingual learners” (MLLs) refers to the same population in federal policy as English learners (ELs). All early childhood settings across Rhode Island are responsible for supporting MLLs in cultivating cultural, linguistic, and intellectual strengths through integrated content and language instruction, enrichment opportunities, and a whole-child approach to teaching and learning.

Early Intervention. Children under the age of three are eligible for EI if they have a “single established condition” known to lead to developmental delay (e.g., very low birth weight, Down Syndrome, etc.) or if they have a significant developmental delay in one or more areas of development. One of the goals of EI is to provide support to families so their children can develop to their fullest potential and to best accomplish this, services are provided in places where children usually play or take part in daily activities. Anyone may refer a child to EI such as a pediatrician, social worker, childcare provider, friend, or family member. Referrals for EI should be made directly to the individual Early Intervention agency listed here.

Early Childhood Special Education. Early Childhood Special Education is a federal and state mandated program for young children with developmental delays and disabilities. It refers to the range of special education services that apply specifically to children between the ages of 3 and 5, prior to Kindergarten. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and the Rhode Island Regulations Governing the Education of Children with Disabilities ensure that all children with disabilities, including children with developmental delays, who require special education to meet their educational needs are provided with appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE) in accordance with their individual needs. To be eligible for special education children must be referred, evaluated, and determined eligible for services. This document describes the process of responding to referrals, conducting evaluations, and determining eligibility in alignment with the Division for Early Childhood (DEC) Recommended Practices.

RIDE envisions an educational landscape in which all children in Rhode Island will enter Kindergarten developmentally, social-emotionally, and educationally ready to succeed, putting them on a path to read proficiently by 3rd grade (ECCE Strategic Plan, 2021).

From birth, children are curious and primed for learning. Child growth and development is particularly rapid during the first five years of life and are influenced by a complex combination of factors including all of their interactions with the physical and social world (Kupcha-Szrom, 2011; Center on the Developing Child, 2012). RIDE envisions high-quality early learning environments and curricula as having a focus on the whole child, recognizing that development is integrated, and occurs simultaneously across all domains. It is through play-based learning experiences that children will develop, generate knowledge of the larger world, and begin to acquire qualities for lifetime learning. As such, the goal of the Early Learning framework is to create conditions in which all of our state’s youngest learners will have the opportunity to be immersed in a play-based environment supported by high- quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment practices that are aligned with the Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS).

Through continued interagency collaboration with the Department of Human Services, Department of Health, Department of Children, Youth, and Families, the Executive Office of Health and Human Services, and the Governor’s Office, RIDE will establish research-based policy and guidance to build a strong foundation for early learners’ future education, relationships, and development.

The purpose of the Early Learning framework is to provide guidance to educators, curriculum leaders, instructional coaches, district and program administrators, educator preparation providers and professional learning providers, and family and community members around the implementation of the Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS), particularly as it relates to the design and use of curriculum materials, instruction, and assessment for programs serving children ages Birth through five. The framework streamlines a vertical application of standards and assessment across the early learning continua, increase opportunities for all children to engage in developmentally appropriate learning experiences, and ultimately support educators and families in making decisions that prioritize children’s learning. These uses of the curriculum frameworks align to the overarching commitment to ensuring all children have access to high-quality and developmentally appropriate curriculum, instruction, and assessment that prepares them to succeed in kindergarten and beyond.

Success Criteria

The following five guiding principles are the foundation for Rhode Island's Early Learning Curriculum Framework. The guiding principles speak to the coherence of an educational system grounded in rigorous standards. This framework integrates recommendations and resources that are evidence-based, specific to the standards, support the needs of all learners – including multilingual learners and differently-abled students, and link to complementary RIDE policy, guidance and initiatives to create a vision of a coherent, high-quality, educational system.

The Guiding Principles for the Early Learning Framework are intended to frame the guidance within this document around the use and implementation of standards to drive curriculum, instruction, and assessment within a multitiered system of supports (MTSS). These principles include the following:

- Standards are the bedrock of an interrelated system involving high-quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

- High-quality curriculum materials align to the standards and in doing so must be accessible, culturally responsive, supportive of multilingual learners, developmentally appropriate, equitable, as well as leverage children’s’ strengths as assets.

- High-quality, equitable, and developmentally appropriate instruction is data driven and relies on evidence-based assessment, drawing on families and communities as resources.

- High-quality assessments must be valid and reliable, aligning to the standards and equitably providing educators with opportunities to monitor child learning and development. Play is the primary means children use to demonstrate early learning accomplishments.

- All aspects of a standards-based educational system, including policies, practices, and resources, must work together to support all children, including multilingual learners and those that are differently-abled.

RIDE has previously defined curriculum as a “standards-based sequence of planned experiences where students practice and achieve proficiency in content and applied learning skills. Curriculum is the central guide for all educators as to what is essential for teaching and learning so that every student has access to rigorous academic experiences.” Building off of this definition, RIDE also identifies specific components that comprise a complete curriculum. These include the following:

- Goals: Goals within a curriculum are the standards-based benchmarks or expectations for teaching and learning. Most often, goals are made explicit in the form of a scope and sequence of skills to be addressed. Goals must include the breadth and depth about what a student is expected to learn.

- Methods: Methods are instructional decisions, approaches, and routines that teachers use to engage all students in meaningful learning. These choices support the facilitation of learning experiences to promote a student’s ability to understand and apply content and skills. Methods are differentiated to meet student needs and interests, task demands, and learning environment. They are also adjusted based on ongoing review of student progress towards meeting the goals.

- Materials: Materials are the tools and resources selected to implement methods and achieve the goals of the curriculum. They are intentionally chosen to support a student's learning, and the selection of resources should reflect student interest, cultural diversity, world perspectives, and address all types of diverse learners. To assist childcare centers, family childcare homes, Head Starts, and Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state with the curriculum selection process, RIDE identified an “Approved List of Pre-Kindergarten Curricula.” The intent of this list is to provide programs with the ability to choose a high-quality curriculum that best fits the needs of its students, teachers, and community and is aligned with the Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS) as well as a department-developed rubric to demonstrate alignment to the expectations for high-quality curriculum in the State. See the “Selecting High-Quality Materials” section on page 18 for more information on RI’s List of Approved Curricula for Children ages 3-5 years.

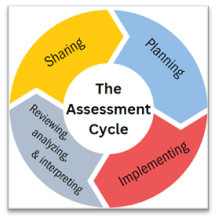

- Assessment: Assessment in a curriculum is the ongoing process of gathering information about a student’s learning. This includes a variety of ways to document what the student knows, understands, and can do with their knowledge and skills. Information from assessment is used to make decisions about instructional approaches, teaching materials, and academic supports needed to enhance opportunities for the student and to guide future instruction.

Another way to think about curriculum, and one supported by many experts, is that a well-established curriculum consists of three interconnected parts all tightly aligned to standards: the intended (or written) curriculum, the lived curriculum, and the learned curriculum (e.g., Kurz, Elliott, Wehby, & Smithson, 2010). Additionally, a cohesive curriculum should ensure that teaching and learning is equitable, culturally responsive, and offers students multiple means through which to learn and demonstrate proficiency.

The written curriculum refers to the learning experiences and other supports included in the curriculum guide. This aligns with the ‘goals’ and ‘materials’ components described above. Given this, curriculum materials (lesson plans, books, learning activities) do not comprise a curriculum on their own, but rather are the resources that help to implement it. They also establish the foundation of students’ learning experiences. The written curriculum should provide students with opportunities to engage in learning experiences that build on their background experiences and cultural and linguistic identities while also exposing students to new experiences and cultural identities outside of their own. The written curriculum is crucial in building a foundation for high-quality learning; however, it is important to remember that it is only as good as how it is used and/or implemented.

The lived curriculum refers to everything that children actually experience in the learning setting, including how the teacher delivers curriculum, how children experience the curriculum, and how learning is assessed. In other words, the lived curriculum is defined by the quality of instructional practices that are applied when implementing the written curriculum. This aligns with the “methods” section in RIDE’s curriculum definition. The lived curriculum must promote instructional engagement by affirming and validating students’ home culture and language as well as provide opportunities for integrative and interdisciplinary learning. Learning experiences should be instructed through an equity lens, providing all children with a rich, high-quality learning experience.

Finally, the learned curriculum refers to how much of and how well the intended curriculum is learned and how fully students meet the learning goals as defined by the standards. This is often defined by the validity and reliability of assessments, as well as by student achievement, their work, and performance on tasks. The learned curriculum should reflect a commitment to the expectation that all students can access and attain widely held developmental milestones aligned with the RIELDS. Ultimately, the learned curriculum is an expression and extension of the written and lived curriculum and should promote critical consciousness in both educators and students, providing opportunities for educators and students to improve systems for teaching and learning in the school community.

Key Takeaways

- First, the written curriculum (goals and HQCMs) must be firmly grounded in the standards and include a robust set of HQCMs that all teachers know how to use to design and implement instruction and assessment for students.

- Second, the characteristics of a strong lived curriculum include consistent instructional practices and implementation strategies that take place across classrooms that are driven by standards, evidence-based practices, learning tasks for students that are rigorous and engaging, and a valid and reliable system of assessment.

- Finally, student learning and achievement are what ultimately define the overall strength of a learned curriculum, including how effectively students are able to meet the standards.

The early learning and K-12 content area frameworks are designed to provide consistent guidance around how to use standards to support the selection and use of high-quality curriculum materials, evidence-based instructional practices, as well as valid and reliable assessments - all in an integrated effort to equitably maximize learning for all students. The curriculum frameworks can also be used to inform decisions about appropriate foci for professional learning, certification, and evaluation of active and aspiring teachers and administrators.

The curriculum frameworks include information about research-based, culturally responsive, and equitable pedagogical approaches and strategies for use during implementation of high-quality curriculum materials and assessments to scaffold, develop, and assess the skills, competencies, and knowledge called for by the state standards.

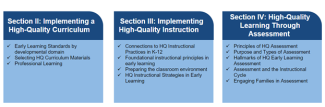

Organization of the Curriculum Frameworks:

- Section 2 lists the standards and provides a range of resources to help educators understand and apply them. Section 2 also addresses how standards support the selection and implementation of high-quality curriculum materials.

- Section 3 provides guidance and support around building high-quality, standards-aligned instruction in the early learning classroom.

- Section 4 offers resources and support for using high-quality, standards-aligned early learning assessment.

In sum, each curriculum framework, in partnership with high-quality curriculum materials, informs decisions at the classroom, school/program, and district/community level about curriculum material use, instruction, and assessment in line with current standards and with a focus on facilitating equitable and culturally responsive learning opportunities for all students.

Summary of Section Structure

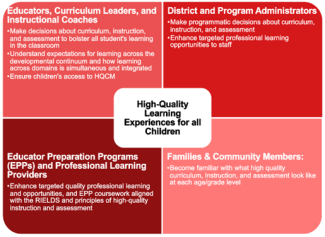

The primary audiences for the information and resources in the Early Learning Curriculum Framework are educators in Rhode Island who make decisions and implement practices that impact students’ opportunities for learning in line with standards. This means that the primary audience includes educators, instructional leaders, education coordinators, and district and program administrators.

Below are examples of how RIDE envisions the guidance and resources within this framework being used. These examples are not exhaustive by any measure and are intended to give early childhood stakeholders an initial understanding of how to practically begin thinking about how to implement and use this framework to inform their daily practice.

Educators, Curriculum Leaders, and Instructional coaches such as curriculum coordinators, education coordinators, and principals can use the curriculum frameworks as a go-to resource for understanding how the Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards align with the high-quality curriculum materials (HQCMs) that have been adopted in their district/program and to make decisions about instruction and assessment that bolster all children’s learning opportunities. For example, the frameworks can be used to:

- Unpack and internalize age-level standards and alignment of standards across domains;

- Analyze HQCMs and assessment(s) adopted in the district or program and understand how the standards are applied within curriculum, instruction, and assessment;

- Norm on high-quality instructional practices that are specific to early learning and practices aligned with K-12;

- Guide decisions related to instruction and assessment given the developmental expectations for children articulated in the standards and the HQCMs; and,

- Plan universally designed instruction and aligned scaffolds that ensure all children can engage meaningfully with developmentally appropriate instruction.

District and program administrators can use the curriculum frameworks to calibrate their understanding of what high-quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment should look like within and across disciplines and use that understanding as a guide to:

- Make resources available to educators, families, and other stakeholders in support of child learning and development;

- Norm “what to look for” in classrooms as evidence that children are receiving a rigorous and engaging instructional experience; and

- Structure conversations with teachers and families about high-quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

Educator Preparation Programs and Professional Learning Providers can use the curriculum frameworks to enhance targeted quality professional learning opportunities for the field. For example, the frameworks can be used to:

- Enhance educator or aspiring educator knowledge about the standards and pedagogical approaches in Rhode Island;

- Roll out a vision for curriculum and instruction in the district or program, followed by curriculum-specific professional learning;

- Build capacity of educators and aspiring educators to engage in meaningful intellectual preparation to support facilitation of strong lessons;

- Aid educators and aspiring educators in making sense of the structure, organization, and pedagogical approaches used in different curriculum materials; and,

- Build capacity of educators and aspiring educators to address individual learning needs of students through curriculum-aligned scaffolds.

Families and community members can use the curriculum frameworks to become familiar with what curriculum, instruction, and assessment should look like at each age and stage of development. For example, the frameworks can be used to:

- Generate awareness of what high-quality, standards-aligned and developmentally appropriate early childhood curriculum, instruction and assessment should look like;

- Support decision-making and selection of care-based settings based on knowledge of high-quality early childhood practices; and,

- Support home- and community-based (extracurricular) experiences that are play-based, standards-aligned, and developmentally appropriate.

RIDE has developed curriculum frameworks for a variety of K-12 content areas including mathematics, science and technology, ELA/literacy, History and Social Studies, World Languages, and the arts. While the Early Learning framework addresses the comprehensive development of children across content areas, there is coherence across all curriculum frameworks, including a common grounding in principles focused on connections to content standards and providing equitable and culturally responsive learning opportunities through curriculum resources, instruction, and assessment. The curriculum frameworks also explicitly connect to RIDE’s work in other areas including, but not limited to, multilingual learners, differently-abled students, college and career readiness, and culturally responsive and sustaining practices. Below is a brief overview of how this and the other curriculum frameworks are organized, as well as a summary of how the specific curriculum frameworks overlap and connect to each other.

|

Section |

What is common across the content area curriculum frameworks? |

What is content-specific in each content area’s curriculum framework? |

|---|---|---|

|

Section 1: Introduction |

Section 1 provides an overview of the context, purpose, and expectations related to the curriculum framework. |

Each curriculum framework articulates a unique vision for how the framework can support high-quality teaching and learning. |

|

Section 2: Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum |

The introduction to this section defines how RIDE defines HQCMs in relation to standards. The final part of this section explains how HQCMs are selected in RI and provides related tools. |

The middle section of each curriculum framework has content-specific information about the standards behind curriculum resources and the vision for student success in the targeted content area. The final part of this section includes some specific information about the HQCMs for the targeted content area. |

|

Section 3: Implementing High-Quality Instruction |

This section provides an overview of how high-quality instruction is guided by standards and introduces five cross-content instructional practices for high-quality instruction. This section also includes guidance and tools to support high-quality instruction and professional learning across content areas. |

This section expands upon the cross-content instructional practices by providing content-specific information about instructional practices. This section also includes more specific guidance and tools for considering instruction and professional learning in the targeted content area. |

|

Section 4: High-Quality Learning Through Assessment |

The curriculum frameworks are all grounded in common information described here about the role of formative and summative assessment and how these align with standards. Some standard tools and guidance for assessment in any content area are also provided. |

Content-specific guidance about tools and resources for assessing students in the targeted content area are included in this section. |

Kurz, A., Elliott, S. N., Wehby, J. H., & Smithson, J. L. (2010). Alignment of the Intended, Planned, and Enacted Curriculum in General and Special Education and Its Relation to Student Achievement. The Journal of Special Education, 44(3), 131-145. Retrieved from Alignment-of-the-Intended-Planned-and-Enacted-Curriculum-in-General-and-Special-Education-and-Its-Relation-to-Student-Achievement.pdf (researchgate.net)

Rhode Island Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. (2021). Together Through Opportunity: Pathways to Student Success: Rhode Island's Strategic Plan for PK-12 Education, 2021-2025. Retrieved from RIDEStrategicPlan_2021-2025.pdf.

Section II: Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum

Having access to high-quality curriculum materials is an important component of increasing equitable access to a rigorous education that prepares every student for college and careers. In answer to this national movement to increase access through high-quality materials, the State of Rhode Island, in 2019, passed RIGL§ 16.22.30-33. The legislation requires that all RI LEAs adopt high-quality curriculum materials in schools for children in grades K-12 that are (1) aligned with academic standards, (2) aligned with the curriculum frameworks, and (3) aligned with the statewide standardized test(s), where applicable. While the legislation does not explicitly include early learning in scope, it is critical that programs serving young children adopt high-quality curriculum materials in alignment with the Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS) as research indicates the positive influence that a high-quality and developmentally appropriate early childhood education has on child developmental outcomes.

RIDE uses a variety of factors to determine high-quality curriculum materials, primarily using information from EdReports, a non-profit, independent organization that uses teams of trained teachers to conduct reviews of English Language Arts (ELA), mathematics, and science curricula. At the moment, EdReports exclusively reviews and reports on curriculum materials serving children in grades K-12. With regards to early learning, the Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center (ECLKC) through the Administration for Children & Families release the Curriculum Consumer Reports, which provide review summaries and ratings of comprehensive infant and toddler, preschool, family childcare, and home-based childcare curricula against the Head Start Program Performance Standards (HSPPS) and other standards for high-quality curricula (e.g., NAEYC). The conclusions drawn from these reports may not be entirely applicable when vetting curriculum against individual state’s standards for early childhood development as state’s standards for early childhood and the Head Start Program Performance Standards may differ. As a result, many states develop their own processes for evaluating and approving early learning curriculum. These processes most typically involve a) analyzing the alignment between an early learning curriculum and state standards b) vetting curriculum against a state-developed rubric containing additional indicators that are indicative of high-quality. It is critical that the adoption of high-quality early learning curricula include considerations of the needs of the children that they serve. Selection is only the starting point in the larger process of adoption and implementation. Early learning programs should consider curriculum adoption and implementation as an iterative process where the efficacy of a curriculum is reviewed and evaluated at the program level on an ongoing basis.

While the standards describe what students should know and be able to do, they do not dictate the manner by which they should be taught, or the materials used to teach and assess them (NGA & CCSSO, 2010). Curriculum materials, when aligned to the standards, provide students with varied opportunities to gain the knowledge and skills outlined by the standards. Assessments, when aligned to the standards, have the goal of understanding how student learning is progressing toward acquiring proficiency in the knowledge and skills outlined by the standards as delivered by the curriculum through instruction (CSAI, 2018).

No set of age-level standards can reflect the great variety of abilities, needs, learning rates, and achievement levels in any given classroom. The standards define neither the support materials that some students may need, nor the advanced materials that others should have access to. It is also beyond the scope of the standards to define the full range of support appropriate for multilingual learners and children that are differently-abled. Still, all students must have the opportunity to learn and meet the same high standards if they are to access the knowledge and skills that will be necessary in their lives. The standards should be read as allowing for the widest possible range of students to participate fully from the outset with appropriate accommodations to ensure equitable access, particularly those from historically underserved populations (MDOE, 2017).

Having access to high-quality curriculum materials is an important component of increasing equitable access to a rigorous education that prepares every student for college and careers.

The 2023 Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS) are designed to provide guidance to families, teachers, and administrators on what children should know and be able to do as they enter kindergarten. They are intended to be inclusive and developmentally appropriate for all children – multilingual learners, children with special health care needs, children that are differently-abled, and children who are typically developing – recognizing that all children may meet age-level expectations as indicated in the RIELDS.

The RIELDS articulate shared expectations for young children’s development across 9 distinct domains: Physical and Motor, Social and Emotional, Language, Literacy, Cognitive, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies, and Creative Arts development. Further, they provide a common language for measuring progress toward achieving specific learning goals (Kendall 2003; Kagan & Scott-Little, 2004). The RIELDS extend educational expectations to infants and toddlers, and they are integrated with preschool early learning standards to create a seamless birth to 60-month continuum and are aligned with K-12 Rhode Island Core Standards for Mathematics, ELA/Literacy, and Social Studies, the Next Generation Science Standards, and the Head Start Child Development and Early Learning Frameworks. The standards are to be used for the purposes of:

- Guiding early educators in the selection of curriculum

- Informing families about learning milestones

- Providing a framework for implementing high-quality early childhood programs

- Promoting optimal early learning trajectories.

While the RIELDS represent expectations for all children, each child will reach the standard milestones at their own pace and in their own way. Therefore, to meet the RIELDS, individual children will require different types and intensities of support across domains. The RIELDS are therefore not intended to be used as specific teaching practices or materials, as a checklist of competencies, nor as a stand-alone curriculum or program: rather, the standards are intended to represent the expectations for children’s learning and development and are to serve as a guide for selecting curriculum and assessment tools.

Organization of the RIELDS

Rhode Island’s Early Learning and Development Standards are organized into domains, components, Standards, and Examples:

| Domains: represent the broad areas of early learning |

Physical and Motor development Social and Emotional development Language development Literacy development Cognitive Development Mathematics development Science development Social Studies development Creative Arts development |

| Components: specific areas within a domain |

Domain: Physical health and motor development

|

| Standards: general categories of competencies, behaviors, knowledge, and skills that children develop in increasing degrees and with increasing sophistication as they grow |

Domain: Physical and Motor Development

|

| Examples: establish the specific developmental benchmarks for the competencies, behaviors, knowledge, and skills that most children possess or exhibit at a particular age for each learning goal. Seen altogether, the examples depict the progression of development over time ranging from Birth through 60 months. |

Domain: Physical and Motor Development

|

|

Early Learning Continuum: |

The early learning and development standards outline a Birth to 60-month continuum, with six developmental benchmarks. |

Developmental Domains

As noted above, the RIELDS are organized across 9 central domains, by which expectations for children’s growth and development are indicated.

Below is a summary of each developmental domain found in the RIELDS.

Physical Health and Motor Development

The emphasis in this domain is on physical health and motor development as an integral part of children’s overall well-being. The healthy development of young children is directly related to practicing healthy behaviors, strengthening large and small muscles, and developing strength and coordination. As their gross and fine motor skills develop, children experience new opportunities to explore and investigate the world around them. Conversely, physical health challenges can impede a child’s development and are associated with poor child outcomes. As such, physical development is critical for development and learning in all other domains. The components within this domain address health and safety practices, gross motor development, and fine motor development.

Children with physical challenges may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting gross and fine motor goals; for example, by pedaling an adaptive tricycle, navigating a wheelchair, or feeding themselves with a specialized spoon. Children that are differently abled may meet these same goals in a different way, often at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, or in a different order than their peers. When observing how children demonstrate what they know and can do, teachers must consider appropriate adaptations and modifications, as necessary. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the physical health and motor development of all children. It is important to remember that while this domain represents general expectations for physical health and motor development, each child will reach individual standards at their own pace and in their own way.

Social and Emotional Development.

Social and emotional development encompasses young children’s evolving capacity to form close and positive adult and peer relationships; to actively explore and act on the environment in the process of learning about the world around them; and express a full range of emotions in socially and culturally appropriate ways. These skills, developed in early childhood, are essential for lifelong learning and positive adaptation. A child’s temperament (traits that are biologically based and that remain consistent over time) plays a significant role in development and should be carefully considered when applying social and emotional standards. Healthy social and emotional development benefits from consistent, positive interactions with educators, parents/primary caregivers, and other familiar adults who appreciate each child’s individual temperament. This appreciation is key to promoting positive self-esteem, confidence, and trust in relationships. The components within this domain address children’s relationships with others—adults and other children—their personal identity and self-confidence, and their ability to regulate their emotions and behavior.

All children, including multilingual learners and children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting social and emotional goals; for example, children with visual impairments and/or children from other cultures may vary in direct eye contact and demonstrate their interest in and need for human contact in other ways, such as through acute listening and touch. Children that are differently abled may initiate play through use of subtle cues, at a different pace or with a different degree of accomplishment. In general, the presence of a disability may cause a child to demonstrate alternate ways of meeting social and emotional goals. The goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. When observing how children respond in relationships, teachers must consider appropriate adaptations and modifications, as necessary. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the social and emotional development as well as the cultural and experiential backgrounds of all children.

It is important to remember that healthy social/emotional development goes hand in hand with cross-domain learning and development. Children’s development of a self-awareness and affirmation, for example, is strongly linked to their learning in Social Studies (e.g., Self, Family, and Community). Their development of emotional recognition and regulation contributes to their development of cognitive skills (e.g., Attention and Inhibitory Control) and their abilities to persist at learning activities in language, literacy, mathematics, and science. Successful experiences in the content areas also positively contribute to children’s social/emotional development.

Language Development.

The development of children’s early language skills is critically important for their future academic success. Language development indicators reflect a child’s ability to understand increasingly complex language (receptive language skills), a child’s increasing proficiency when expressing ideas (expressive language skills), and a child’s growing understanding of and ability to follow appropriate social and conversational rules. The components within this domain address receptive and expressive language, pragmatics, and English language development specific to multilingual learners. As a growing number of children live in households where the primary spoken language is not English, this domain also addresses the language development of multilingual learners. Unlike most of the other progressions in this document, however, specific age ranges do not define the indicators for English language development (or for development in any other language). Multilingual learners are exposed to multiple languages for the first time at different ages. As a result, one child may start the process of developing second-language skills at birth and another child may start at four, making the age thresholds inappropriate. So instead of using age ranges, the RIELDS use research-based stages to outline a child’s progress in sequential English language development. It is important to note that there is no set time for how long it will take a given child to progress through these stages. Progress depends upon the unique characteristics of the child, their exposure to English in the home and other environments, the child’s motivation to learn English, and other factors.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of language development. If a child is deaf or hard of hearing, for example, that child may demonstrate progress through gestures, signs, symbols, pictures, augmentative and/or alternative communication devices as well as through spoken words. Children that are differently abled may also demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the same goals, often meeting them at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers. When observing how children demonstrate what they know and can do, the full spectrum of communication options—including the use of American Sign Language and other low- and high-technology augmentative/assistive communication systems—should be considered. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the language development of all children. When considering Principles of UDL, consider the variation in social and conversational norms across cultures. Crosstalk and eye-contact, for example may have varying degrees of acceptability in different cultures.

Literacy Development.

Development in the domain of literacy serves as a foundation for reading and writing acquisition. The development of early literacy skills is critically important for children’s future academic and personal success. Yet children enter kindergarten varying considerably in these skills; and it is difficult for a child who starts behind to close the gap once they enter school (National Early Literacy Panel, 2008). The components within this domain address phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, print awareness, text comprehension and interest, and emergent writing.

As a growing number of children live in households where the primary spoken language is not English, this domain also addresses the literacy development of multilingual learners. However, specific age thresholds do not define the indicators for literacy development in English, unlike most of the other developmental progressions. Children who become multilingual learners are exposed to English (in this country) for the first time at different ages. As a result, one child may start the process of developing English literacy skills very early in life and another child not until age four, making the age thresholds inappropriate. So instead of using age ranges, the RIELDS use research-based stages to outline a child’s progress in sequential English literacy development. It is important to note that there is no set time for how long it will take a given child to progress through these stages. Progress depends upon the unique characteristics of the child, their exposure to English in the home and other environments, the child’s motivation to learn English, and other factors.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of literacy development. For example, a child with a visual impairment will demonstrate a relationship to books and tactile experiences that is significantly different from that of children who can see. As well, children with other special needs and considerations may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, in a different way, with a different degree of accomplishment, or in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different.

Cognitive Development.

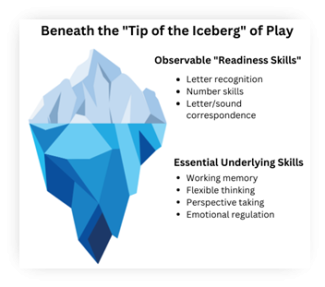

Development in the domain of cognition involves the processes by which young children grow and change in their abilities to pay attention to and think about the world around them. Infants and young children rely on their senses and relationships with others; exploring objects and materials in different ways and interacting with adults both contribute to children’s cognitive development. Everyday experiences and interactions provide opportunities for young children to learn how to solve problems, differentiate between familiar and unfamiliar people, attend to things they find interesting even when distractions are present, and understand how their actions affect others. Research in child development has highlighted specific aspects of cognitive development that are particularly relevant for success in school and beyond. These aspects fall under a set of cognitive skills called executive function and consist of a child’s working memory, attention and inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility. Together, these skills function like an “air traffic control system,” helping a child manage and respond to the vast body of the information and experiences they are exposed to daily. The components within this domain address logic and reasoning skills, memory and working memory, attention and inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of

cognitive development. For example, a child with a physical disability may require adaptive toys to explore cause-and-effect relationships and a child with a speech impairment may use augmentative and/or alternative communication devices to retell a familiar story or activity. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, or in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the cognitive development of all children.

Mathematics

The development of mathematical knowledge and skills contributes to children’s ability to make sense of the world and to solve mathematical situations they encounter in their everyday lives. Knowledge of basic math concepts and the skill to use math operations to solve mathematical situations are fundamental aspects of school readiness and are predictive of later success in school and in life. The components within this domain address number sense and quantity; number relationships and operations; classification and patterning; measurement, comparison, and ordering; and geometry and spatial sense.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of mathematics development. For example, a child who is blind may begin to identify braille numbers and a child with a physical disability may identify numerals through use of an eye gaze. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best serve the mathematics development of all children.

Science

From the moment they are born, children share many of the characteristics of young scientists. They are curious and persistent explorers who use their senses to investigate, observe, and make sense of the world around them. As they grow and develop, they become increasingly adept at using the practices that scientists use to learn about the world—including asking questions, planning, and carrying out investigations, collecting and analyzing data, and constructing explanations based on evidence. Like young engineers, they also become increasingly skilled at identifying and addressing problems that arise in their play and designing and testing solutions, especially in their constructive play with objects and materials. The RIELDS science domain includes a standard focused on the science and engineering practices as well as standards that address children’s learning of basic concepts in physical, Earth/space and life science. Children deepen their understanding of these concepts gradually over time and many experiences. Crosscutting concepts, including cause and effect, patterns, and structure and function (e.g., how something is made relates to how it is used) are also incorporated and embedded within each standard. Engaging in the science and engineering practices in the service of building their understanding of science concepts creates many opportunities for children to develop mathematics knowledge and abilities as well as skills in the physical, language, literacy, cognitive, and social-emotional domains including essential, but less readily observable executive function skills such as working memory, attention to tasks, and cognitive flexibility.

All children come to a school or community-based setting with a variety of prior experiences in science can take part in and learn science. In relation to the standards, each child will express their development and learning in different ways, at different times, and at different paces. Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of the science domain. For example, a child with a cognitive delay may require additional hands-on-learning opportunities to generalize science content and a child with an expressive language delay may require pictures or photographs to contribute observations and predictions after classroom-based investigations. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments, adopting curricula, and facilitating children’s experiences in ways that best support science learning for all children. It is important to remember that the practices of science incorporate a wide range of skills across the domains of development and learning. For example, the practices include multiple opportunities for children to engage in productive talk and exercise language and literacy skills as they formulate questions, explore and describe observable phenomena, record findings, and discuss their emerging ideas with others. As you plan science experiences it will be important to think broadly about children’s levels of development and learning and consider their day-to-day family, home, and community experiences so that you implement and facilitate science experiences that are meaningful and responsive to children’s lives, interests, cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and leverage their strengths, and support areas for growth in context.

Social Studies

The field of social studies is interdisciplinary, and intertwines concepts relating to government, civics, economics, history, sociology, and geography. Through social studies, children can explore and develop an understanding of their place within and relationship to family, community, environment, and the world. Social studies learning supports children’s emerging understanding of social rules, and their ability to recognize and respect personal and collective responsibilities as necessary components for a fair and just society. By engaging with familiar adults and peers through the course of their everyday lives, children across the birth through five continua are introduced to the different perspectives that they and others share and to life within their community – such as an understanding of principles of community care, supply and demand, occupations, and currency (Civics & Government and Economics). In addition, social studies learning helps children to develop an awareness of the passage of time and diversity (History), and place (Geography). As children learn about their own history, the history of others, and the diversity in the environment in which they live, they place themselves within a broader context of the world around them and can think beyond the walls of their home and early childhood classroom.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of social studies development. For example, a child with a physical disability may require environmental modifications, such as a lower cubby or extensions on the sink faucets to follow classroom routines such as putting away a backpack upon arrival and washing hands after a meal. A child with a cognitive delay might need picture cues to recall information about the immediate past. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the social studies development of all children. It is important to remember that as social studies learning experiences and assessments are planned to reflect upon the diversity of the children the classroom and how the components within this domain can be represented in ways that are meaningful to children’s individuality, their family, their homes, and their community as well as the ways in which Social Studies development relates to development in other domains. The development of personal responsibility and group membership, for example, have strong links to Social Emotional Development.

Creative Arts

The arts provide children with a vehicle and organizing framework to express ideas and feelings. Music, movement, drama, and visual arts stimulate children to use words, manipulate tools and media, and solve problems in ways that simultaneously convey meaning and are aesthetically pleasing. As such, participation in the creative arts is an excellent way for young children to learn and use creative skills in other domains. The component within this domain addresses a child’s willingness to experiment with and participate in the creative arts.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of creative arts development. Children who are non-verbal, for example, may focus on activities that are rhythmic rather than vocal, and children who are deaf or hard of hearing will be able to respond to music by feeling the vibrations in the air. Children with other special needs and considerations may reach many of these same goals but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support participation in creative arts for all children.

In March 2021, RIDE issued a Request for Information from publishers of evidence-based, comprehensive, and content/domain-specific curriculum for children ages three to five to align with the RIELDS. The review of the curriculum was executed through a two-tiered process: first, with general alignment with the RIELDS and with evidence-based and theoretical methodology. Curricula in alignment with these sections of the rubric moved forward to the second phase of review where it was assessed for alignment with other metrics of high-quality in the early learning context (e.g., classroom materials, child assessment system, developmentally appropriate practice, usability). The curriculum alignment and endorsement process additionally considered elements of differentiated supports present in the materials submitted (e.g., curriculum supports for multilingual learners, children that are differently abled, younger 3-year-olds, children transitioning to kindergarten).

Through submissions received, RIDE has been able to endorse a final list of curricula that is RIDE-approved. The assessment and the final curriculum endorsement are intended to be used for the purpose of selecting curricula for use in childcare centers, family childcare homes, Head Starts, Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state. RI Pre-K programs are required to adopt a curriculum that is RIDE-approved. While this is only compulsory for RI Pre-K programs, it is encouraged that other programs utilize a RIDE-approved curricula to best support children’s learning and development in alignment with the RIELDS.

The Selecting and Implementing a High-quality Curricula In Rhode Island: A Guidance Document: outlines the provisions of RIGL§ 16.22.30-33 with regard to adopting high-quality curriculum and includes a list of approved curricula for Early Learning as of January 2021 (Appendix C). The Early Learning and Development Standards webpage on the RIDE website provides further information on Rhode Island’s Approved List of Pre-Kindergarten Curricula, and opportunities and resources for program leaders, educators, families, and other early learning-invested community members.

At RIDE, we are cognizant of the importance of being a part of the global community and support simultaneous multilingual learning. Many of RIDE’s endorsed curricula are offered in both English and in Spanish. If early learning programs are interested in offering a supplemental foreign language learning curricula and assessment, they must ensure that the supplemental programs selected align with the RIELDS and the instructional and assessment guidance provided in Sections III and IV of this framework.

Tools to support understanding of the RIELDS and selecting of High-Quality Curriculum

| RESOURCE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS) | This standards document includes developmental and learning standards for children ages Birth through 60 months. The standards represent the development of the whole-child with focus on standards across 9 developmental domains: Physical and Motor, Social and Emotional, Language, Literacy, Mathematics, Cognitive, Science, Social Studies, and Creative Arts development. |

|

RIELDS Fun Family Activities Cards & |

These family resources offer information and enjoyable ways to support the development and learning of young children, based on the RIELDS. The toolkit resource provides educators with tips on how to use the Fun Family Activity cards to encourage families in supporting their child’s learning and development. |

| RIELDS Professional Development Trainings

|

This webpage lists all of the professional development offerings aligned with the RIELDS that are accepting registration at a given time. RIELDS Professional Development courses are available to all educators that are interested in deepening their knowledge of the RIELDS, the curriculum and planning process, instructional cycle, and implementing a program that is aligned with the standards. |

| Selecting and Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum in Rhode Island: A Guidance Document | This curriculum selection guidance document outlines the provisioners of RIGL § 16.22.30-33 with regarding adopting high-quality curriculum and includes a list of approved curriculum for K-12 as well as pre-kindergarten (Appendix C). |

| RI’s Approved List of Pre-Kindergarten Curricula

|

This approved curriculum list indicates curriculum for children ages 3 to 5 that are aligned with the RIELDS as well as against a department-developed rubric that demonstrate alignment to expectations for high-quality curriculum in the state of Rhode Island. This list is intended to influence the selection of high-quality curriculum materials in child care centers, family child care homes, Head Starts, Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state. |

| 2021 Early Learning and Development Standards Curriculum Alignment: Guidance Document | This guidance document provides information to educational stakeholders in child care centers, family child care homes, Head Starts, Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state, on RIDE’s curriculum alignment and endorsement process. |

Section III: Implementing High-Quality Instruction

As described in Sections 1 and 2 of this framework, while robust standards and high-quality curriculum materials (HQCMs) are essential to providing all students the opportunities to learn what they need in college and a career of their choosing, high-quality instruction is also needed. Standards define what students should know and be able to do. HQCMs that are aligned to the standards provide educators with a roadmap and tools for how students can acquire that knowledge and skill. It is high-quality instruction that makes the curriculum come alive for students. High-quality instruction gives all students access and opportunity for acquiring the knowledge and skills defined by the standards with a culturally responsive and sustaining approach. “When educators have great instructional materials, they can focus their time, energy, and creativity on meeting the diverse needs of students and helping them all learn and grow. (Instruction Partners Curriculum Support Guide Executive Summary, page 2).

The process of translating a high-quality curriculum into high-quality instruction involves much more than opening a box and diving in. This is because no single set of materials can be a perfect match for the needs of all the students that educators will be responsible for teaching. Therefore, educators must intentionally plan an implementation strategy in order to have the ability to translate high-quality curriculum materials into high-quality instruction. Some key features to attend to include:

-

Set systemic goals for curriculum implementation and establish a plan to monitor progress,

-

Determine expectations for educator use of HQCMs,

-

Craft meaningful opportunities for curriculum-based embedded professional learning,

-

Factor in the need for collaborative planning and coaching; and,

-

Develop systems for collaboratively aligning HQCMs to the needs of multilingual students and differently abled students.

Thus, with a coherent system in place to support curriculum use, educators will be well-positioned to attend to the nuances of their methods and make learning relevant and engaging for the diverse interests and needs of their students.

Given the above, what constitutes high-quality instruction? In short, high-quality instruction is defined by the practices that research and evidence have demonstrated over time as the most effective in supporting student learning. In other words, when teaching is high-quality, it embodies what the field of education has found to work the best. Therefore, this section provides a synthesis of research- and evidence-based practices that the Rhode Island Department of Education believes characterizes high-quality instruction in Early Learning. This section begins by describing the high-quality instructional practices that apply across content areas and grades with details and examples that explain what these instructional practices look like in Early Learning, and also explains other specific instructional practices that are at the core of high-quality instruction in Early Learning. The instructional practices articulated in this section are aligned with and guided by best practices for multilingual learners and for children that are differently abled, and specific information and resources are provided about how to support all students in their learning while drawing on their individual strengths. These instructional practices also contribute to a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) in which all students have equitable access to strong, effective core instruction that supports their academic, behavioral, and social emotional outcomes. This section on instruction ends with a set of resources and tools that can facilitate high-quality instruction and professional learning about high-quality instruction, including tools that are relevant across content areas and grade levels and those that are specific to Early Learning. In reviewing this section, use Part 2 to understand what high-quality instruction should look like for all students in Early Learning.

In order to effectively implement high-quality curriculum materials, as well as ensure that all students have equitable opportunities to learn and prosper, it is essential that educators are familiar with and routinely use instructional practices and methods that are research- and evidenced-based. In developing the K-12 curriculum frameworks, RIDE established five practices that are essential to effective teaching and learning and are common across all disciplines. Part 2 begins by outlining these high-quality instructional practices and then dives deeper into instructional practices that are essential and more specific to early learning educational settings, servicing children ages birth through 5 years. Call-out boxes are embedded throughout this section drawing connections between high-quality instruction in the early learning context with the five high-quality instructional practices identified for all disciplines. While these call-out boxes represent a few of these notable connections, readers may notice other parallels between the high-quality instructional practices and the early learning instructional guidance.

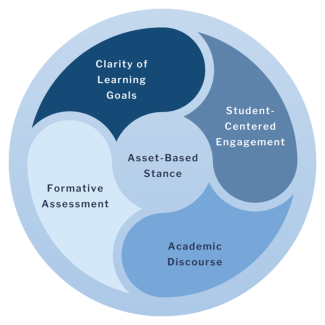

High-Quality Instruction in All Disciplines

Below are five high-quality instructional practices that RIDE has identified as essential to the effective implementation of standards and high-quality curriculum in all content areas (see figure to the right). These practices are emphasized across all the curriculum frameworks and are supported by the design of the high-quality curriculum materials. They also strongly align with the instructional framework for multilingual learners, the high-leverage practices (HLPs) for children that are differently abled, and RIDE’s educator evaluation system. Below is a brief description of each practice.

Asset-Based Stance

Teachers routinely leverage students’ strengths and assets by activating prior knowledge and connecting new learning to the culturally and linguistically diverse experiences of students while also respecting individual differences.

Clear Learning Goals

Teachers routinely use a variety of strategies to ensure that students understand the following:

- What they are learning (and what proficient work looks like),

- Why they are learning it (how it connects to what their own learning goals, what they have already learned and what they will learn), and

- How they will know when they have learned it.

Student-Centered Engagement

Teachers routinely use techniques that are student-centered and foster high levels of engagement through individual and collaborative sense-making activities that promote practice, application in increasingly sophisticated settings and contexts, and metacognitive reflection.

Academic Discourse

Teachers routinely facilitate and encourage student use of academic discourse through effective and purposeful questioning and discussion techniques that foster rich peer-to-peer interactions and the integration of discipline-specific language into all aspects of learning.

Formative Assessment

Teachers routinely use qualitative and quantitative assessment data (including student self-assessments) to analyze their teaching and student learning in order to provide timely and useful feedback to students and make necessary adjustments (e.g., adding or removing scaffolding and/or assistive technologies, identifying the need to provide intensive instruction) that improve student outcomes.

High-Quality Instruction in Early Learning

This section discusses several high-quality instructional practices that RIDE has identified essential to the effective use of the early learning standards (RIELDS) and implementation of high-quality curriculum. These instructional practices are organized within three key areas:

- Set the Stage for Learning – Foundational early learning instructional principles that will “set the stage” for supporting children’s development and learning throughout the school year.

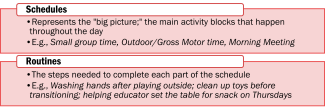

- Get Ready: Prepare the Environment – Important considerations for setting up the physical classroom environment and schedule in ways that are developmentally appropriate, mindful, and responsive to the needs of the children served.

- Facilitating Children’s Learning: Instructional Strategies – Specific instructional strategies that support children’s growth and development of 21st Century Skills, including critical thinking and problem-solving, communication, collaboration, and creativity (“The 4 C’s).

RIDE recognizes and is committed to providing all children with equitable learning opportunities that enable them to achieve their full potential as engaged learners and valued members of society. This framework is informed by the National Association for the Education of Young Children’s (NAEYC) Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education position statement, and includes considerations related to creating a caring, equitable community of engaged learners; establishing reciprocal relationships with families; and observing, documenting and assessing children’s learning and development, all of which early childhood educators may use in practice to promote an inclusive and equitable space for the state’s youngest learners. Furthermore, the topics addressed in this framework will integrate considerations related to promoting universal design, encompassing the birth through five age spans, and supporting multilingual learners and children that are differently abled throughout.

Set the Stage for Learning

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), defines Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) as:

“Methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approaching to joyful, engaged learning. Educators implement developmentally appropriate practice by recognizing the multiple assets all young children bring to the early learning program as unique individuals and as members of families and communities. Building on each child’s strengths – and taking care not to harm any aspect of each child’s physical, cognitive, social, or emotional well-being – educators design and implement learning environments to help all children achieve their full potential across all domains of development across all content areas. DAP recognizes and supports each individual as a valued member of the learning community. As a result, to be developmentally appropriate, practices must also be culturally, linguistically, and ability appropriate for each child.” (NAEYC, 2020, p.5).

Developmentally appropriate practice requires early childhood educators to seek out and gain knowledge and understanding using three core considerations:

- Commonality – current research and understandings of processes of child development and learning that apply to all children, including the understanding that all development and learning occur within specific social, cultural, linguistic, and historical contexts.

- Example: Educators have a strong foundational understanding of the Rhode Island and Development Standards (RIELDS) and are also learners who consistently seek out research-based resources to improve their teaching and knowledge of child development and learning

- Individuality – the characteristics and experiences unique to each child, within the context of their family and community, that have implications for how best to support their development and learning.

- Example: Educators are cognizant of the unique characteristics of each child that they are supporting (e.g., identities, interests, strengths, abilities, languages, needs…etc.); educators engage with families in meaningful ways early and often

- Context – everything discernible about the social and cultural contexts for each child, each educator, and the program as a whole.

- Example: Educators understand how different contexts within a child’s identity and life (e.g., race/ethnicity, language, gender, class, ability, family composition, socioeconomic status…etc.) intersect and impact their development and learning.

Through a deep understanding of the three considerations above, educators determine how curricula may be scaffolded and adapted to facilitate each child’s progress toward their individual learning goals. Developmentally appropriate practice involves flexibility in opportunities, materials, and teaching strategies offered to support each child’s individual learning needs.

Connections with K-12 Content Area Frameworks: Student-Centered Engagement

Through student-centered engagement educators provide students with opportunities for individual and collaborative sense-making. When early childhood educators create intentional, play-based learning experiences, they provide children with opportunities to activate prior knowledge and expose them to academic concepts and social experiences in increasingly complex ways.

DAP Teaching Strategies. NAEYC identifies 10 effective and Developmentally Appropriate teaching strategies. These teaching strategies cannot be achieved all at once; rather, an effective educator or family childcare provider is expected to remain flexible and observant, consider what children already know and are able to do and determine which teaching strategy is appropriate to use in a particular situation. The 10 DAP teaching strategies are defined below with respective examples:

|

DAP Teaching Strategy |

Example |

|

Acknowledge what children do or say. Let children know that we have noticed by giving positive attention, sometimes through comments, sometimes through just sitting nearby and observing. |

“Thanks for your help, Kavi.”

“You found another way to show the number 5.” |

|

Encourage persistence and effort rather than just praising and evaluating what the child has done. |

[To an infant walking towards you]: “One more step – you’ve got this!”

“You’re thinking of lots of words to describe the dog in the story. Let’s keep going!” |

|

Give Specific Feedback rather than general comments. |

“The beanbag didn’t get all the way to the hoop, James, so you might try throwing it harder” |

|

Model attitudes, ways of approaching problems, and behavior towards others, showing children rather than just telling them. |

[To a toddler when another child wants his ball]: “There are more balls here, should we get him one?” [And walks over to get the ball for the other child]

Educator remarks, “Hmmm. that didn’t work and I need to think about why.” |

|

Demonstrate the correct way to do something. This usually involves a procedure that needs to be done in a certain way. |

Assist a toddler with handwashing, talking about it as you do it.

When following a recipe for making playdough, demonstrate how to measure out flour using a measuring cup so they can see what it looks like to measure a dry ingredient. |

|

Create or Add Challenge so that a task goes a bit beyond what the children can already do. |

For infants, move a block that they are reaching for further away or bring it a little closer so they can successfully reach it.